1. What Is a Concept?

There are no simple concepts. Every concept has components and is defined by them. It therefore has a combination [chiffre*]. It is a multiplicity, although not every multiplicity is conceptual. There is no concept with only one component. Even the first concept, the one with which a philosophy "begins," has several components, because it is not obvious that philosophy must have a beginning, and if it does determine one, it must combine it with a point of view or a ground [une raison]. Not only do Descartes, Hegel, and Feuerbach not begin with the same concept, they do not have the same concept of beginning. Every concept is at least double or triple, etc. Neither is there a concept possessing every component, since this would be chaos pure and simple. Even so-called universals as ultimate concepts must escape the chaos by circumscribing a universe that explains them (contemplation, reflection, communication). Every concept has an irregular contour defined by the sum of its components, which is why, from Plato to Bergson, we find the idea of the concept being a matter of articulation, of cutting and cross-cutting. The concept is a whole because it totalizes its components, but it is a fragmentary whole. Only on this condition can it escape the mental chaos constantly threatening it, stalking it, trying to reabsorb it.

단순한 개념은 없습니다. 모든 개념에는 구성 요소가 있으며 구성 요소에 의해 규정됩니다. 따라서 개념에는 [쉬프레*]라는 조합이 있습니다. 모든 다양체가 개념인 것은 아니지만 그것은 다양체입니다. 하나의 구성 요소만 있는 개념은 없습니다. 철학이 '시작' 되는 첫 번째 개념조차도 여러 구성 요소를 가지고 있는데, 그 이유는 철학이 반드시 시작을 가져야 한다는 것도 분명하지 않고, 만약 시작을 결정한다면 그것을 관점이나 근거[une raison]와 결합해야만 하기 때문입니다. 데카르트, 헤겔, 포이어바흐는 같은 개념으로부터 시작하지 않았을 뿐만 아니라 시작에 대한 개념도 동일하지 않습니다. 모든 개념은 적어도 이중 또는 삼중 개념입니다. 모든 구성 요소를 가진 개념도 존재하지 않는데, 그렇다면 순수하고 단순한 카오스가 될 것이기 때문입니다. 소위 궁극적 개념들이라고 불리는 보편적 개념들조차도 그것들의 설명을 가능하게 하는 하나의 우주(관조, 성찰, 소통) 내로 한정되어야만 카오스에서 벗어날 수 있습니다. 모든 개념은 그 구성 요소들의 합에 의해 정의되는 불규칙한 윤곽을 가지고 있기 때문에 플라톤에서 베르그송에 이르기까지 개념이라는 아이디어는 분절, 자르기 및 교차의 문제입니다. 개념은 그 구성 요소들을 총체화하기 때문에 전체이지만 그것은 파편화된 전체입니다. 이 조건에서만 그것은 끊임없이 그것을 위협하고, 스토킹하고, 재 흡수하려고 시도하는 정신적 카오스에서 벗어날 수 있습니다.

On what conditions is a concept first, not absolutely but in relation to another? For example, is another person [autrui] necessarily second in relation to a self? If so, it is to the extent that its concept is that of an other(a subject that presents itself as an object) which is special in relation to the self: they are two components. In fact, if the other person is identified with a special object, it is now only the other subject as it appears to me; and if we identify it with another subject, it is me who is the other person as I appear to that subject. All concepts are connected to problems without which they would have no meaning and which can themselves only be isolated or understood as their solution emerges. We are dealing here with a problem concerning the plurality of subjects, their relationship, and their reciprocal presentation. Of course, everything changes if we think that we discover another problem: what is the nature of the other person's position that the other subject comes to "occupy" only when it appears to me as a special object, and that I in turn come to occupy as special object when I appear to the other subject? From this point of view the other person is not anyone-neither subject nor object. There are several subjects because there is the other person, not the reverse. The other person thus requires an a priori concept from which the special object, the other subject, and the self must all derive, not the other way around. The order has changed, as has the nature of the concepts and the problems to which they are supposed to respond. We put to one side the question of the difference between scientific and philosophical problems. However, even in philosophy, concepts are only created as a function of problems which are thought to be badly understood or badly posed (pedagogy of the concept).

어떤 조건에서 개념은 다른 개념과 관련하여 절대적이지는 않지만 우선적인가요? 예를 들어, 다른 사람['타자']은 자아와 관련하여 필연적으로 이차적인가요? 그렇다면 타자라는 개념은 자아와의 관계에서 특수한 타인(객체로서 자신을 드러내는 주체)이라는 개념의 범위 내에서만 가능합니다: 그들은 두 가지 구성 요소입니다. 사실 다른 사람을 그 특수한 객체와 동일시하면 그것은 단지 나에게 나타나는 다른 주체일 뿐이고, 그것을 또 다른 주체와 동일시하면 그 주체에게 나타나는 다른 사람이 바로 나입니다. 모든 개념들은 그 개념이 없으면 의미가 없는, 그리고 그 해결책이 드러날 때만 분리되거나 이해될 수 있는 문제와 연결되어 있습니다. 우리는 여기서 주체의 복수성과 그들의 관계, 그리고 그들의 상호 표상에 관한 문제를 다루고 있습니다. 물론 우리가 또 다른 문제를 발견한다고 생각하면 모든 것이 달라집니다. 다른 주체가 나에게 특수한 객체로 나타날 때만 "점유" 하고, 차례로 내가 다른 주체에게 나타날 때 특수한 객체로 점유하는 이 타자의 위치의 본질은 무엇일까요? 이 관점에서 타자는 주체도 객체도 아니고 그 누구도 아닙니다. 주체가 여러 개 있는 것은 타자가 있기 때문이지 그 반대가 아닙니다. 따라서 타자는 특수한 객체, 다른 주체, 자아가 모두 파생되어야 하는 선험적 개념을 필요로 하는 것이지 그 반대가 아닙니다. 따라서 그들이 대응해야 하는 개념들과 문제들의 본성이 바뀜에 따라 그 순서도 바뀌었습니다. 우리는 과학적 문제와 철학적 문제의 차이에 대한 질문을 한쪽으로 치워두었습니다. 그러나 철학에서도 개념은 잘못 이해되거나 잘못 제기된 것으로 생각되는 문제의 함수로서만 만들어집니다(개념의 교육학).

Let us proceed in a summary fashion: we will consider a field of experience taken as a real world no longer in relation to a self but to a simple "there is." There is, at some moment, a calm and restful world. Suddenly a frightened face looms up that looks at something out of the field. The other person appears here as neither subject nor object but as something that is very different: a possible world, the possibility of a frightening world. This possible world is not real, or not yet, but it exists nonetheless: it is an expressed that exists only in its expression-the face, or an equivalent of the face. To begin with, the other person is this existence of a possible world. And this possible world also has a specific reality in itself, as possible: when the expressing speaks and says, "I am frightened," even if its words are untruthful, this is enough for a reality to be given to the possible as such. This is the only meaning of the "I" as linguistic index. But it is not indispensable: China is a possible world, but it takes on a reality as soon as Chinese is spoken or China is spoken about within a given field of experience. This is very different from the situation in which China is realized by becoming the field of experience itself. Here, then, is a concept of the other that presupposes no more than the determination of a sensory world as condition. On this condition the other appears as the expression of a possible. The other is a possible world as it exists in a face that expresses it and takes shape in a language that gives it a reality. In this sense it is a concept with three inseparable components: possible world, existing face, and real language or speech.

요약하자면, 우리는 현실 세계로 받아들인 경험의 영역을 더 이상 자아와의 관계가 아닌 단순한 "있다"로 간주할 것입니다. 어느 찰나 고요하고 평온한 세계가 있습니다. 그러다 갑자기 장 너머의 무언가를 바라보는 겁에 질린 얼굴이 떠오릅니다. 여기서 타자는 주체도 객체도 아닌 매우 다른 어떤 것, 즉 가능한 세계, 무서운 세계의 가능성으로 나타납니다. 이 가능한 세계는 실재화되거나 오지 않았지만 그럼에도 불구하고 존재합니다. 그것은 얼굴, 또는 얼굴에 상응하는 등가물로서의 표현 안에서만 존재하는 표현된 것입니다. 우선 타자는 이 가능한 세계의 존재입니다. 그리고 이 가능한 세계는 가능한 세계로서 그 자체로 구체적인 실재를 가지고 있습니다: 표현자가 "나는 무섭다"라고 말할 때, 그 말이 진실이 아닐지라도, 이것만으로도 가능한 세계에 실재가 부여되기에는 충분합니다. 이것이 언어적 지표로서 '나'의 유일한 의미입니다. 그러나 그것은 필수 불가결한 것은 아닙니다: 중국은 가능한 세계이지만, 주어진 경험의 영역에서 중국어를 말하거나 중국에 대해 이야기하는 순간 실재가 됩니다. 이는 중국이 경험의 장 자체가 되어 실재화되는 상황과는 매우 다릅니다. 여기서 타자라는 개념은 감각 세계를 조건짓는 것 이상을 전제하지 않습니다. 이 조건에서 타자는 가능한 것의 표현으로 나타납니다. 타자는 가능한 세계를 표현하는 얼굴로 존재하고 그것에 실재를 부여하는 언어로 형상화되기 때문에 가능한 세계입니다. 이런 의미에서 그것은 분리할 수 없는 세 가지 요소들로 구성된 개념입니다: 가능한 세계, 현존하는 얼굴, 현실의 언어 또는 말입니다.

Obviously, every concept has a history. This concept of the other person goes back to Leibniz, to his possible worlds and to the monad as expression of the world. But it is not the same problem, because in Leibniz possibles do not exist in the real world. It is also found in the modal logic of propositions. But these do not confer on possible worlds the reality that corresponds to their truth conditions (even when Wittgenstein envisages propositions of fear or pain, he does not see them as modalities that can be expressed in a position of the other person because he leaves the other person oscillating between another subject and a special object). Possible worlds have a long history. In short, we say that every concept always has a history, even though this history zigzags, though it passes, if need be, through other problems or onto different planes. In any concept there are usually bits or components that come from other concepts, which corresponded to other problems and presupposed other planes. This is inevitable because each concept carries out a new cutting-out, takes on new contours, and must be reactivated or recut.

물론 모든 개념에는 역사가 있습니다. 이 타자 개념은 라이프니츠, 그의 가능한 세계, 그리고 세계의 표현으로서의 모나드로 거슬러 올라갑니다. 그러나 라이프니츠에서 가능성은 현실 세계에 존재하지 않기 때문에 같은 문제가 아닙니다. 그것은 명제들의 양상 논리에서도 발견됩니다. 그러나 이것들은 가능한 세계에 진리 조건에 해당하는 실재를 부여하지 않습니다(비트겐슈타인이 공포나 고통의 명제를 상정할 때조차도, 그는 타자를 다른 주체와 특수 대상 사이에서 진동하는 타자로 남겨두기 때문에 그것들을 타자의 위치에서 표현할 수 있는 양상들로 간주하지 않습니다). 가능한 세계는 오랜 역사를 가지고 있습니다. 요컨대, 우리는 이 역사가 지그재그로 이어지더라도, 필요하다면 다른 문제나 다른 차원을 통과하더라도 모든 개념은 항상 역사를 가지고 있다고 말합니다. 모든 개념에는 일반적으로 다른 문제에 상응하고 다른 차원을 전제로 하는 다른 개념에서 나온 조각이나 구성 요소가 있습니다. 이는 각 컨셉이 새로운 잘라내기를 수행하고 새로운 윤곽을 취하며 다시 활성화하거나 재절단해야 하기 때문에 불가피한 현상입니다.

On the other hand, a concept also has a becoming that involves its relationship with concepts situated on the same plane. Here concepts link up with each other, support one another, coordinate their contours, articulate their respective problems, and belong to the same philosophy, even if they have different histories. In fact, having a finite number of components, every concept will branch off toward other concepts that are differently composed but that constitute other regions of the same plane, answer to problems that can be connected to each other, and participate in a co-creation. A concept requires not only a problem through which it recasts or replaces earlier concepts but a junction of problems where it combines with other coexisting concepts. The concept of the Other Person as expression of a possible world in a perceptual field leads us to consider the components of this field for itself in a new way. No longer being either subject of the field or object in the field, the other person will become the condition under which not only subject and object are redistributed but also figure and ground, margins and center, moving object and reference point, transitive and substantial, length and depth. The Other Person is always perceived as an other, but in its concept it is the condition of all perception, for others as for ourselves. It is the condition for our passing from one world to another. The Other Person makes the world go by, and the "I" now designates only a past world ("I was peaceful"). For example, the Other Person is enough to make any length a possible depth in space, and vice versa, so that if this concept did not function in the perceptual field, transitions and inversions would become incomprehensible, and we would always run up against things, the possible having disappeared. Or at least, philosophically, it would be necessary to find another reason for not running up against them. It is in this way that, on a determinable plane, we go from one concept to another by a kind of bridge. The creation of a concept of the Other Person with these components will entail the creation of a new concept of perceptual space, with other components to be determined (not running up against things, or not too much, will be part of these components).

반면에 개념에는 같은 차원에 위치한 개념과의 관계를 포함하는 '되기'도 있습니다. 여기서 개념들은 다른 역사들을 가지고 있더라도 서로 연결되고, 서로를 지탱하며, 그들의 윤곽을 조정하고, 각각의 문제를 명료화하며, 같은 철학에 속합니다. 실제로 모든 개념은 유한한 수의 구성 요소를 가지고 있기 때문에 다르게 구성된, 그러나 동일한 차원 내의 다른 영역을 구성하는 다른 개념을 향해 분기하고 서로 연결될 수 있는 문제들에 답하며 일종의 공동 창조에 참여하게 됩니다. 하나의 개념은 이전 개념을 재조명하거나 대체하는 문제뿐만 아니라 공존하는 다른 개념과 결합되는 문제들의 접점을 필요로 합니다. 지각 장에서 가능한 세계를 표현하는 타자라는 개념은 이 장의 구성 요소들 자체를 새로운 방식으로 고려하게 합니다. 타자는 더 이상 장의 주체나 장의 객체가 아닌 주체와 객체뿐만 아니라 형상과 배경, 여백과 중심, 운동하는 대상과 준거점, 타동사와 실사, 길이와 깊이가 재분배되는 조건이 됩니다. 타자는 항상 타자로 인식되지만, 그 개념에서 타자는 우리 자신들과 마찬가지로 다른 것들에 대한 모든 지각의 조건입니다. 그것은 우리가 한 세계에서 다른 세계로 넘어가기 위한 조건입니다. 타자는 세상을 지나가게 하고, '나'는 이제 과거의 세계("나는 평화로웠다")만을 지칭합니다. 예를 들어, 타자는 공간에서 모든 길이를 가능한 깊이로 만들기에 충분하며 그 반대의 경우도 마찬가지입니다. 따라서 이 개념이 지각 영역에서 작동하지 않으면 전환과 반전이 이해 될 수 없게 되고 우리는 항상 가능한 것이 사라진 사물에 직면하게 될 것입니다. 또는 적어도 철학적으로 그들과 맞닥뜨리지 않는 다른 이유를 찾아야 할 것입니다. 이런 식으로 결정 가능한 차원에서 우리는 일종의 다리를 통해 한 개념에서 다른 개념으로 이동합니다. 이러한 구성 요소를 가진 타자 개념의 창조는 다른 구성 요소를 결정해야하는 새로운 지각 공간 개념의 창조를 수반 할 것입니다 (사물에 부딪히지 않거나 너무 많이 부딪히지 않는 것이 이러한 구성 요소의 일부가 될 것입니다).

We started with a fairly complex example. How could we do otherwise, because there is no simple concept? Readers may start from whatever example they like. We believe that they will reach the same conclusion about the nature of the concept or the concept of concept. First, every concept relates back to other concepts, not only in its history but in its becoming or its present connections. Every concept has components that may, in turn, be grasped as concepts (so that the Other Person has the face among its components, but the Face will itself be considered as a concept with its own components). Concepts, therefore, extend to infinity and, being created, are never created from nothing. Second, what is distinctive about the concept is that it renders components inseparable within itself. Components, or what defines the consistency of the concept, its endoconsistency, are distinct, heterogeneous, and yet not separable. The point is that each partially overlaps, has a zone of neighborhood [zone de voisinage*], or a threshold of indiscernibility, with another one. For example, in the concept of the other person, the possible world does not exist outside the face that expresses it, although it is distinguished from it as expressed and expression; and the face in turn is the vicinity of the words for which it is already the megaphone. Components remain distinct, but something passes from one to the other, something that is undecidable between them. There is an area ab that belongs to both a and b, where a and b "become" indiscernible. These zones, thresholds, or becomings, this inseparability, define the internal consistency of the concept. But the concept also has an exoconsistency with other concepts, when their respective creation implies the construction of a bridge on the same plane. Zones and bridges are the joints of the concept.

우리는 상당히 복잡한 예로 시작했습니다. 간단한 개념이 없는데 달리 어떻게 할 수 있을까요? 독자들은 자신이 좋아하는 예시에서 시작할 수 있습니다. 우리는 그들이 개념의 본질 또는 개념에 대한 개념에 대해 동일한 결론에 도달할 것이라고 믿습니다. 첫째, 모든 개념은 그것의 역사뿐만 아니라 그것의 되기 또는 현재의 연관성에서도 다른 개념들을 참조합니다. 모든 개념에는 차례로 개념들로 포착될 수 있는 구성 요소가 있습니다(따라서 타자는 그 구성 요소 중 얼굴을 가지고 있지만, 얼굴은 그 자체로 고유한 구성 요소를 가진 개념으로 간주될 수 있습니다). 따라서 개념은 무한대로 확장되고, 만들어지지만 결코 무에서 생성되지 않습니다. 둘째, 개념의 특징은 그 구성 요소들이 개념 내에서 분리될 수 없도록 만든다는 점입니다. 구성 요소, 혹은 개념의 지속성을 정의하는 요소인 그것의 내적 지속성은 구별되고 이질적이지만 아직 분리할 수는 없습니다. 요점은 각각이 부분적으로 겹치고, 다른 요소와 이웃하는 지대[존 드 보아지*], 혹은 식별 불가능한 임계점을 가지고 있다는 것입니다. 예를 들어, 타자라는 개념에서 가능한 세계는 얼굴로부터 표현된 것과 표현으로 구별됨에도 불구하고 그것을 표현하는 얼굴 바깥에 존재하지 않으며, 결국 얼굴은 이미 확성기 역할을 하는 말의 근방입니다. 구성 요소들은 구별되지만 그들 사이에서 결정될 수 없는 무언가가 하나에서 다른 것으로 전달됩니다. a와 b가 구분할 수 없게 "되는", a와 b에 모두 속하는 영역 ab가 있습니다. 이러한 지대들, 임계점들, 또는 되기들, 이러한 분리 불가능성이 개념의 내적 지속성을 정의합니다. 그러나 개념은 다른 개념들과도 외적 지속성을 가지는데, 각 개념들의 창조가 같은 차원 위에서 구축되는 다리를 암시할 때 그렇습니다. 지대들과 다리들은 개념의 관절들입니다.

Third, each concept will therefore be considered as the point of coincidence, condensation, or accumulation of its own components. The conceptual point constantly traverses its components, rising and falling within them. In this sense, each component is an intensive feature, an intensive ordinate [ordonnée intensive*], which must be understood not as general or particular but as a pure and simple singularity(“a” possible world, "a" face, "some" words) that is particularized or generalized depending upon whether it is given variable values or a constant function. But, unlike the position in science, there is neither constant nor variable in the concept, and we no more pick out a variable species for a constant genus than we do a constant species for variable individuals. In the concept there are only ordinate relationships, not relationships of comprehension or extension, and the concept's components are neither constants nor variables but pure and simple variations ordered according to their neighborhood. They are processual, modular. The concept of a bird is found not in its genus or species but in the composition of its postures, colors, and songs: something indiscernible that is not so much synesthetic as syneidetic. A concept is a heterogenesis -that is to say, an ordering of its components by zones of neighborhood. It is ordinal, an intension present in all the features that make it up. The concept is in a state of survey [survol] in relation to its components, endlessly traversing them according to an order without distance. It is immediately co-present to all its components or variations, at no distance from them, passing back and forth through them: it is a refrain, an opus with its number (chiffre).

셋째, 각 개념은 그러므로 자체 구성 요소들의 우연, 응축 또는 축적의 지점으로 간주됩니다. 개념적 지점은 끊임없이 구성 요소들을 가로지르며 그들 안에서 상승하고 하강합니다. 이런 의미에서 각 구성 요소는 강도적 특징, 강도적 좌표[오르도네 인텐시브*]로서, 일반적이거나 특수한 것이 아니라 주어진 변수 값이나 상수 함수에 따라 특수화되거나 일반화되는 순수하고 단순한 특이점("하나의" 가능한 세계, "하나의" 얼굴, " 몇몇" 단어)으로 이해되어야 합니다. 그러나 과학의 입장과 달리 개념에는 상수나 가변이 존재하지 않으며, 우리는 가변적인 개체에 대해 상수 종을 선택하지 않는 것처럼 상수 속을 위해 가변적인 종을 선택하지 않습니다. 개념에는 이해나 연장의 관계가 아닌 서수 관계만 존재하며, 개념의 구성 요소들은 상수나 변수가 아니라 인접한 이웃에 따라 정렬된 순수하고 단순한 변이들입니다. 그것들은 과정적이고 모듈적입니다. 새의 개념은 속이나 종이 아니라 새의 자세, 색깔, 노래의 구성에서 발견되는데, 이는 공기억적이지 않은만큼 공감각적이지 않고 식별할 수 없는 무언가입니다. 개념은 이질 발생, 즉 인접한 지대들에 따른 구성 요소들의 순서입니다. 그것은 서수이며, 그것을 이루는 모든 특징들에 나타나는 강도입니다. 이 개념은 구성 요소들과 관련하여 비행[서볼] 상태에 있으며 거리없는 순서에 따라 끝없이 그들을 횡단합니다. 그것은 모든 구성 요소들 또는 변형들에 즉각적으로 공존하며, 그것들과 아무런 거리도 두지 않고 그것들을 앞뒤로 통과합니다: 그것은 리토르넬로이며, 그 셈(쉬프레)을 가진 작품입니다.

The concept is an incorporeal, even though it is incarnated or effectuated in bodies. But, in fact, it is not mixed up with the state of affairs in which it is effectuated. It does not have spatiotemporal coordinates, only intensive ordinates. It has no energy, only intensities; it is anenergetic (energy is not intensity but rather the way in which the latter is deployed and nullified in an extensive state of affairs). The concept speaks the event, not the essence or the thing -pure Event, a hecceity, an entity: the event of the Other or of the face (when, in turn, the face is taken as concept). It is like the bird as event. The concept is defined by the inseparability of a finite number of heterogeneous components traversed by a point of absolute survey at infinite speed. Concepts are "absolute surfaces or volumes," forms whose only object is the inseparability of distinct variations. The "survey" [survol] is the state of the concept or its specific infinity, although the infinities may be larger or smaller according to the number of components, thresholds and bridges. In this sense the concept is act of thought, it is thought operating at infinite(although greater or lesser) speed.

이 개념은 비록 육체에 구현되거나 육체에 효과화 되더라도 비물체적인 개념입니다. 그러나 사실 그것은 그것이 효과화되는 현상과 혼동되지 않습니다. 그것은 시공간적 좌표가 없고 강도적인 직교 좌표만 있습니다. 그것은 에너지가 없고 오직 강도들만 있으며, 무에너지적입니다(에너지는 강도가 아니라 오히려 후자가 연장적인 상황 속에서 전개되고 무효화되는 방식입니다). 개념은 본질이나 사물이 아닌 사건, 즉 순수한 사건, 이것임, 독립체입니다: 타자 또는 얼굴의 사건(차례로 얼굴이 개념으로 받아들여질 때)을 말합니다. 그것은 마치 사건으로서의 새와 같습니다. 개념은 무한한 속도를 가진 절대적인 비행 지점에 의해 횡단되는 유한한 이질적인 구성 요소들의 분리 불가능성에 의해 정의됩니다. 개념은 "절대 표면들 또는 부피들"로, 개별적인 변이들의 분리 불가능성만을 유일한 대상으로 삼고 형상화합니다. "비행"[서볼]은 무한들이 구성 요소들, 임계점들, 그리고 다리들의 수에 따라 더 커지거나 작아질 수 있음에도 불구하고 개념의 상태 혹은 그것의 특정한 무한입니다. 이런 의미에서 개념은 사유의 행위이며, 무한한(크든 작든) 속도로 작동하는 사유입니다.

The concept is therefore both absolute and relative: it is relative to its own components, to other concepts, to the plane on which it is defined, and to the problems it is supposed to resolve; but it is absolute through the condensation it carries out, the site it occupies on the plane, and the conditions it assigns to the problem. As whole it is absolute, but insofar as it is fragmentary it is relative. It is infinite through its survey or its speed but finite through its movement that traces the contour of its components. Philosophers are always recasting and even changing their concepts: sometimes the development of a point of detail that produces a new condensation, that adds or withdraws components, is enough. Philosophers sometimes exhibit a forgetfulness that almost makes them ill. According to Jaspers, Nietzsche, "corrected his ideas himself in order to create new ones without explicitly admitting it; when his health deteriorated he forgot the conclusions he had arrived at earlier." Or, as Leibniz said, "I thought I had reached port; but ... I seemed to be cast back again into the open sea." What remains absolute, however, is the way in which the created concept is posited in itself and with others. The relativity and absoluteness of the concept are like its pedagogy and its ontology, its creation and its self-positing, its ideality and its reality -the concept is real without being actual, ideal without being abstract. The concept is defined by its consistency, its endoconsistency and exoconsistency, but it has no reference: it is self-referential; it posits itself and its object at the same time as it is created. Constructivism unites the relative and the absolute.

따라서 개념은 절대적이면서도 상대적입니다: 그것은 그것 자체의 구성 요소, 다른 개념들, 그것이 규정되는 차원, 그리고 그것이 해결하도록 기대되는 문제들에 대해서는 상대적이지만, 그것이 수행하는 응축, 차원에서 차지하는 자리, 그리고 그것이 문제에 부여하는 조건들을 통해서는 절대적입니다. 전체적으로 보면 그것은 절대적이지만 파편적인 한에서는 상대적입니다. 그것은 비행이나 속도를 통해서는 무한하지만 구성 요소들의 윤곽을 좇는 움직임을 통해서는 유한합니다. 철학자들은 항상 개념을 재구성하고 심지어 변경하기도 합니다: 때로는 구성 요소들을 추가하거나 빼는, 즉 새로운 응축을 만들어내는 세부적인 지점을 개발하는 것만으로도 충분합니다. 철학자들은 때때로 거의 병에 걸릴 정도의 건망증을 보이기도 합니다. 야스퍼스에 따르면 니체는 "새로운 사상을 창조하기 위해 명확하게 인지하지 못한 채 자신의 생각을 스스로 수정했고, 건강이 악화되자 이전에 도달한 결론을 잊어버렸다"고 합니다. 또는 라이프니츠가 말했듯이 "나는 항구에 도착했다고 생각했지만 ... 나는 다시 망망대해로 던져진 것 같았다"라고 말했죠. 그럼에도 불구하고 절대적으로 남아있는 것은 창조된 개념이 그 자체로 그리고 다른 개념과 함께 위치하는 방식입니다. 개념의 상대성과 절대성은 개념의 교육학과 존재론, 그것의 창조와 자기 자리매김, 그것의 이상과 현실, 즉 개념은 현실화되지 않으면서 실제적이고 추상적이지 않으면서 이상적입니다. 개념은 그것의 지속성, 그것의 내포적 지속성 및 외포적 지속성에 의해 정의되지만, 그것은 참조 대상이 없습니다: 그것은 자기 참조적이며, 그것이 창조됨과 동시에 그 자신과 대상을 자리매김합니다. 구축주의는 상대적인 것과 절대적인 것을 통합합니다.

Finally, the concept is not discursive, and philosophy is not a discursive formation, because it does not link propositions together. Confusing concept and proposition produces a belief in the existence of scientific concepts and a view of the proposition as a genuine "intension" (what the sentence expresses). Consequently, the philosophical concept usually appears only as a proposition deprived of sense. This confusion reigns in logic and explains its infantile idea of philosophy. Concepts are measured against a "philosophical" grammar that replaces them with propositions extracted from the sentences in which they appear. We are constantly trapped between alternative propositions and do not see that the concept has already passed into the excluded middle. The concept is not a proposition at all; it is not propositional, and the proposition is never an intension. Propositions are defined by their reference, which concerns not the Event but rather a relationship with a state of affairs or body and with the conditions of this relationship. Far from constituting an intension, these conditions are entirely extensional. They imply operations by which abscissas or successive linearizations are formed that force intensive ordinates into spatiotemporal and energetic coordinates, by which the sets so determined are made to correspond to each other. These successions and correspondences define discursiveness in extensive systems. The independence of variables in propositions is opposed to the inseparability of variations in the concept. Concepts, which have only consistency or intensive ordinates outside of any coordinates, freely enter into relationships of nondiscursive resonance either because the components of one become concepts with other heterogeneous components or because there is no difference of scale between them at any level. Concepts are centers of vibrations, each in itself and every one in relation to all the others. This is why they all resonate rather than cohere or correspond with each other. There is no reason why concepts should cohere. As fragmentary totalities, concepts are not even the pieces of a puzzle, for their irregular contours do not correspond to each other. They do form a wall, but it is a dry-stone wall, and everything holds together only along diverging lines. Even bridges from one concept to another are still junctions, or detours, which do not define any discursive whole. They are movable bridges. From this point of view, philosophy can be seen as being in a perpetual state of digression or digressiveness.

마지막으로, 개념은 담론적이지 않으며 철학은 명제들을 서로 연결하지 않기 때문에 담론적인 형식이 아닙니다. 개념과 명제를 혼동하는 것은 과학적 개념들의 존재에 대한 믿음과 명제를 진정한 '의도'(문장이 표현하는 것)로 보는 관점을 낳습니다. 결과적으로 철학적 개념은 대개 의미가 박탈된 명제로만 나타납니다. 이러한 혼란이 논리를 지배하고 철학에 대한 그것의 유아적인 생각을 설명합니다. 개념들은 그 개념들이 나타나는 문장들에서 추출한 명제들로 대체되는 "철학적" 문법에 따라 측정됩니다. 우리는 끊임없이 대안 명제들 사이에 갇혀 개념이 이미 배제된 중간으로 빠져나갔다는 것을 보지 못합니다. 개념은 전혀 명제가 아니며, 그것은 명제적이지 않고, 명제는 결코 의도/강도가 아닙니다. 명제들은 사건에 관한 것이 아니라 어떤 상황 또는 신체와의 관계, 그리고 이 관계의 조건과 관련된 참조를 통해 정의됩니다. 이러한 조건은 인텐션(의도/강도)를 구성하는 것과는 거리가 멀고 전적으로 연장적인 것입니다. 그것들은 강도적인 좌표를 시공간적 좌표와 에너지 좌표로 강제하는 가로좌표 또는 연속적인 선형화가 형성되는 작업을 의미하며, 그렇게 확정된 집합끼리 서로 대응하도록 만들어집니다. 이러한 연속과 상응은 연장적인 시스템에서 담론성을 정의합니다. 명제에서 변수들의 독립성은 개념에서 변수들의 분리 불가능성과 대립됩니다. 어떤 좌표 밖에서도 지속성이나 강도적인 좌표만을 갖는 개념은 하나의 구성 요소가 다른 이질적인 구성 요소와 함께 개념이 되거나 그들 사이에는 어떤 수준에서도 규모의 차이가 없기 때문에 비담론적 공명의 관계를 자유롭게 맺습니다. 개념들은 각각 그 자체로 진동의 중심들이며, 그 자체로 다른 모든 것들과 연관되어 있습니다. 그렇기 때문에 개념은 서로 일치하거나 상응하는 것이 아니라 공명합니다. 개념이 반드시 일치해야 할 이유는 없습니다. 파편적인 총체로서, 개념들은 불규칙한 윤곽으로 인해 서로 대응하지 않기 때문에 퍼즐의 조각이라고도 할 수 없습니다. 벽을 형성하기는 하지만 그것은 마른 돌담이며 모든 것은 분기하는 선을 따라서만 함께 고정됩니다. 한 개념에서 다른 개념으로 연결되는 다리들도 여전히 교차점 또는 우회로이며 어떠한 담론적인 전체도 정의하지 않습니다. 그들은 움직일 수 있는 다리입니다. 이러한 관점에서 철학은 끊임없는 일탈 또는 탈선의 상태에 있는 것으로 볼 수 있습니다.

The major differences between the philosophical enunciation of fragmentary concepts and the scientific enunciation of partial propositions follow from this digression. From an initial point of view, all enunciation is positional. But enunciation remains external to the proposition because the latter's object is a state of affairs as referent, and the references that constitute truth values as its conditions (even if, for their part, these conditions are internal to the object). On the other hand, positional enunciation is strictly immanent to the concept because the latter's sole object is the inseparability of the components that constitute its consistency and through which it passes back and forth. As for the other aspect, creative or signed enunciation, it is clear that scientific propositions and their correlates are just as signed or created as philosophical concepts: we speak of Pythagoras's theorem, Cartesian coordinates, Hamiltonian number, and Lagrangian function just as we speak of the Platonic Idea or Descartes's cogito and the like. But however much the use of proper names clarifies and confirms the historical nature of their link to these enunciations, these proper names are masks for other becomings and serve only as pseudonyms for more secret singular entities. In the case of propositions, proper names designate extrinsic partial observers that are scientifically definable in relation to a particular axis of reference; whereas for concepts, proper names are intrinsic conceptual personae who haunt a particular plane of consistency. It is not only proper names that are used very differently in philosophies, sciences, and arts but also syntactical elements, and especially prepositions and the conjunctions, "now," "therefore." Philosophy proceeds by sentences, but it is not always propositions that are extracted from sentences in general. At present we are relying only on a very general hypothesis: from sentences or their equivalent, philosophy extracts concepts (which must not be confused with general or abstract ideas), whereas science extracts prospects (propositions that must not be confused with judgments), and art extracts percepts and affects (which must not be confused with perceptions or feelings). In each case language is tested and used in incomparable ways-but in ways that do not define the difference between disciplines without also constituting their perpetual interbreeding.

파편적인 개념에 대한 철학적 언표와 부분적인 명제에 대한 과학적 언표 사이의 큰 차이점은 이 일탈에서 비롯됩니다. 처음의 관점에서 보면 모든 언표는 위치적인 것입니다. 그러나 언표는 명제에 외재적으로 남아 있는데, 왜냐하면 후자의 대상은 참조로서의 상태이고, 참조들은 그 조건으로서 진리 값을 구성하기 때문입니다(비록 이러한 조건들이 대상의 내부에 있다고 하더라도). 반면에 위치적 언표는 철저하게 개념에 내재하는 것으로, 후자의 유일한 대상은 그것의 지속성을 구성하고 그것을 앞뒤로 통과하는 구성 요소들의 분리 불가능성이기 때문입니다. 다른 측면인 창조적 또는 기호화된 언표에 관해서는 과학적 명제들과 그 상관물이 철학적 개념과 마찬가지로 기호화되거나 창조되었다는 것이 분명합니다: 우리가 피타고라스의 정리, 데카르트의 좌표, 해밀턴의 수, 라그랑주의 함수 등을 말하는 것처럼 플라톤 이데아나 데카르트의 코기토 등을 말하는 것이죠. 그러나 고유명사의 사용이 이러한 언표들의 역사적인 연관성을 명확히 하고 확인시켜 주지만, 이러한 고유명사는 다른 되기들의 가면이며 더 비밀스러운 특이한 실체들에 대한 가명 역할을 할 뿐입니다. 명제들의 경우 고유명은 특정한 기준축과 관련하여 과학적으로 정의할 수 있는 외재적인 부분 관찰자를 지정하는 반면, 개념의 경우 고유명은 특정한 지속의 차원을 떠도는 내재적인 개념적 페르소나입니다. 철학, 과학, 예술에서 각기 다르게 사용되는 것은 고유명사뿐만 아니라 통사적인 요소들, 특히 전치사와 접속사 "지금", "그러므로"와 같은 접속사도 마찬가지입니다. 철학은 문장들로 진행되지만, 문장에서 추출되는 것이 일반적으로 항상 명제인 것은 아닙니다. 현재 우리는 매우 일반적인 가설에만 의존하고 있습니다. 철학은 문장 또는 그에 상응하는 등가물들에서 개념(일반적 또는 추상적 아이디어와 혼동해서는 안 됨)을 추출하는 반면 과학은 예상들(판단과 혼동해서는 안 되는 명제들)을 추출하고 예술은 지각들과 변용태들(인식 또는 감정과 혼동해서는 안 됨)을 뽑아냅니다. 각각의 경우 언어는 비교할 수 없는 방식으로 테스트되고 사용되지만, 학문 간의 차이를 정의하지 않으면서도 끊임없는 교배를 구성하는 방식으로 사용됩니다.

Example 1

To start with, the preceding analysis must be confirmed by taking the example of one of the best-known signed philosophical concepts, that of the Cartesian cogito, Descartes's l: a concept of self. This concept has three components-doubting, thinking, and being (although this does not mean that every concept must be triple). The complete statement of the concept qua multiplicity is "I think 'therefore' I am" or, more completely, "Myself who doubts, I think, I am, I am a thinking thing." According to Descartes the cogito is the always-renewed event of thought.

우선, 가장 잘 알려진 기호화된 철학적 개념 중 하나인 데카르트의 코기토, '나', 즉 자아 개념을 예로 들어 앞의 분석을 확인해야 합니다. 이 개념에는 의심, 사고, 존재라는 세 가지 요소가 있습니다(그렇다고 해서 모든 개념이 세 가지여야 한다는 의미는 아닙니다). 이 다중성 개념의 완전한 진술은 "나는 '그러므로' 나라고 생각한다." 또는 더 완벽하게 표현하면 "의심하는 나, 나는 생각한다, 나는 존재한다, 나는 생각하는 것이다."입니다. 데카르트에 따르면 코기토는 끊임없이 갱신되는 사고의 사건입니다.

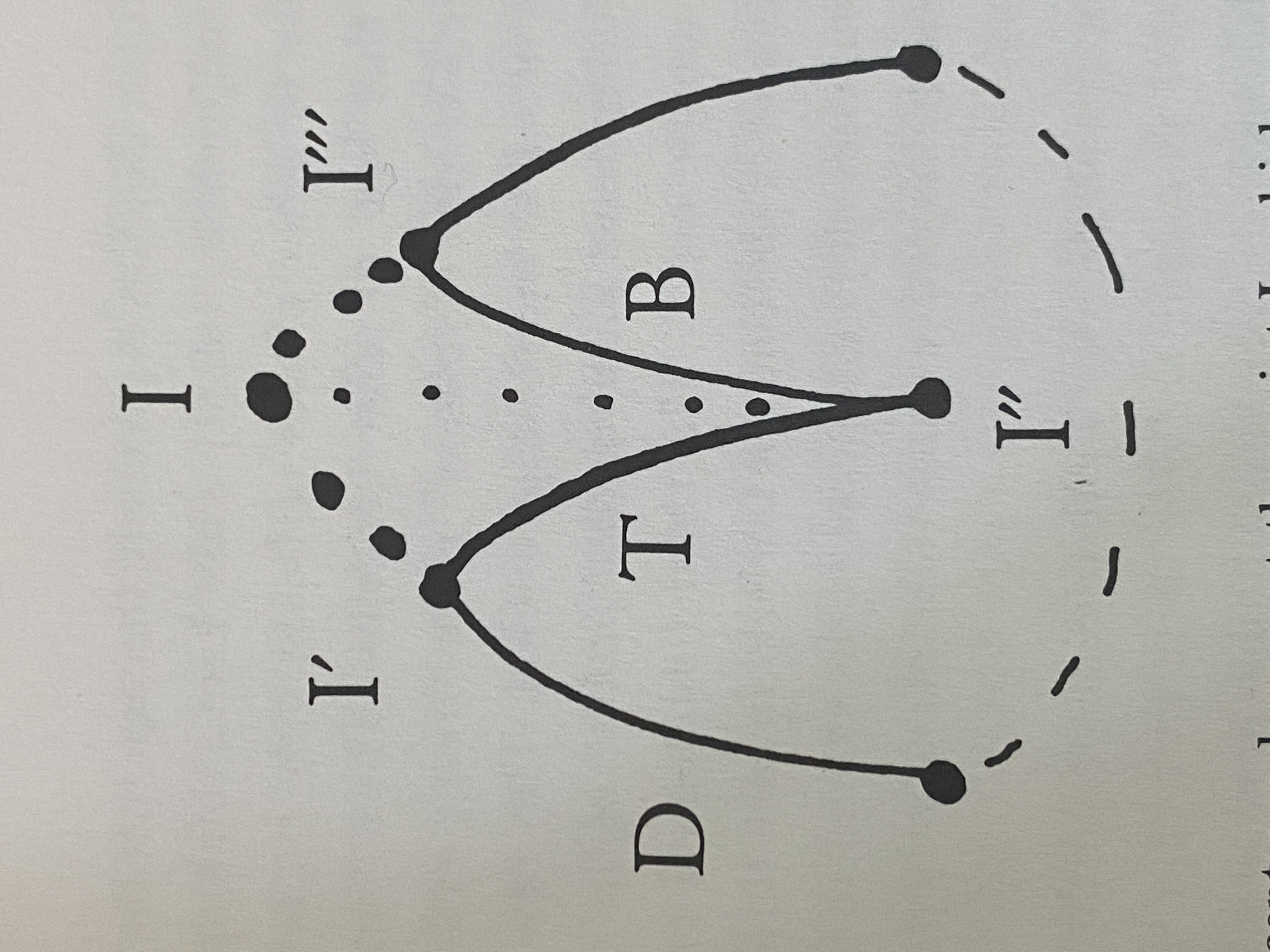

The concept condenses at the point I, which passes through all the components and in which I' (doubting), I" (thinking), and I"' (being) coincide. As intensive ordinates the components are arranged in zones of neighborhood or indiscernibility that produce passages from one to the other and constitute their inseparability. The first zone is between doubting and thinking (myself who doubts, I cannot doubt that I think), and the second is between thinking and being (in order to think it is necessary to be). The components are presented here as verbs, but this is not a rule. It is sufficient that there are variations. In fact, doubt includes moments that are not the species of a genus but the phases of a variation: perceptual, scientific, obsessional doubt (every concept therefore has a phase space, although not in the same way as in science). The same goes for modes of thought-feeling, imagining, having ideas and also for types of being, thing, or substance-infinite being, finite thinking being, extended being. It is noteworthy that in the last case the concept of self retains only the second phase of being and excludes the rest of the variation. But this is precisely the sign that the concept is closed as fragmentary totality with "I am a thinking thing": we can pass to other phases of being only by bridges or crossroads that lead to other concepts. Thus, "among my ideas I have the idea of infinity" is the bridge leading from the concept of self to the concept of God. This new concept has three components forming the "proofs" of the existence of God as infinite event. The third (ontological proof) assures the closure of the concept but also in turn throws out a bridge or branches off to a concept of the extended, insofar as it guarantees the objective truth value of our other clear and distinct ideas.

개념은 나(의심), 나'(생각), 나'(존재)가 일치하는 모든 구성 요소를 통과하는 지점 I에서 응축됩니다. 강도적 좌표로서 구성 요소는 이웃 또는 식별 불가능한 영역으로 배열되어 하나에서 다른 것으로의 통로를 생성하고 분리 불가능성을 구성합니다. 첫 번째 영역은 의심과 생각(의심하는 나 자신, 나는 내가 생각하는 것을 의심할 수 없다) 사이이고, 두 번째 영역은 생각과 존재('생각하기 위해서는 존재해야 한다') 사이입니다. 여기서 구성 요소는 동사로 표시되어 있지만 이것이 규칙은 아닙니다. 여기에는 변형이 있는 것으로 충분합니다. 사실 의심에는 한 속의 종이 아닌 변이의 단계들, 즉 지각적, 과학적, 강박적 의심이 포함됩니다(따라서 모든 개념은 과학과 같은 방식은 아니지만 단계들의 위상 공간을 가지고 있습니다). 생각의 양상들, 즉 느낌, 상상, 생각하기, 그리고 존재, 사물 또는 실체의 유형, 즉 무한한 존재, 유한한 사고 존재, 연장된 존재도 마찬가지입니다. 마지막 경우에 자아 개념은 존재의 두 번째 단계만 유지하고 나머지 변형을 배제한다는 점이 주목할 만합니다. 그러나 이것은 개념이 "나는 생각하는 것" 이라는 단편적인 전체성으로 닫혀 있다는 신호입니다: 우리는 다른 개념으로 이어지는 다리나 교차로를 통해서만 존재의 다른 단계로 넘어갈 수 있습니다. 따라서 "내 생각 중에는 무한이라는 생각이 있다"는 것은 자아 개념에서 신 개념으로 이어지는 다리입니다. 이 새로운 개념은 무한한 사건으로서의 신의 존재에 대한 '증명들'을 구성하는 세 가지 요소로 이루어져 있습니다. 세 번째(존재론적 증명)는 개념의 폐쇄성을 보장하는 동시에 우리의 다른 명확하고 뚜렷한 관념들의 객관적 진리 값을 보장하는 한, 연장된 개념으로 가는 다리 또는 가지를 놓아줍니다.

When the question "Are there precursors of the cogito?" is asked, what is meant is "Are there concepts signed by previous philosophers that have similar or almost identical components but from which one component is lacking, or to which others have been added, so that a cogito does not crystallize since the components do not yet coincide in a self?" Everything seems ready, and yet something is missing. Perhaps the earlier concept referred to a different problem from that of the cogito (a change in problems being necessary for the Cartesian cogito to appear), or it was developed on another plane. The Cartesian plane consists in challenging any explicit objective presupposition where every concept refers to other concepts (the rational-animal man, for example). It demands only a prephilosophical understanding, that is, implicit and subjective presuppositions: everyone knows what thinking, being, and I mean (one knows by doing it, being it, or saying it). This is a very novel distinction. Such a plane requires a first concept that presupposes nothing objective. So the problem is "What is the first concept on this plane, or by beginning with what concept can truth as absolutely pure subjective certainty be determined?" Such is the cogito. The other concepts will be able to achieve objectivity, but only if they are linked by bridges to the first concept, if they respond to problems subject to the same conditions, and if they remain on the same plane. Objectivity here will assume a certainty of knowledge rather than presuppose a truth recognized as preexisting, or already there.

"코기토의 전조가 있는가?"라는 질문의 의미는 "이전 철학자들이 서명했던 개념 중 유사하거나 거의 동일한 구성 요소를 가지고 있지만 한 구성 요소가 부족하거나 다른 구성 요소가 추가되어 아직 구성 요소들이 자아에서 일치하지 않아 코기토로 결정화되지 않은 개념이 있는가?"라는 질문입니다. 모든 것이 준비된 것 같지만 무언가 빠진 것 같습니다. 아마도 이전의 개념은 코기토의 문제와는 다른 문제(데카르트적 코기토가 나타나기 위해 필요한 문제의 변화)로 소급되거나 다른 차원에서 발전된 것일 수 있습니다. 데카르트적 차원은 모든 개념이 다른 개념(예를 들어 이성적 동물적 인간)을 지칭하는 명시적인 객관적 전제에 도전하는 것으로 이루어져 있습니다. 그것은 오직 선철학적 이해, 즉 암묵적이고 주체적인 전제들, 즉 모든 사람이 생각, 존재, 그리고 나라는 것이 무엇을 의미하는지 알고 있습니다(사람은 그것을 행하고, 존재하고, 말함으로써 알 수 있습니다). 이것은 매우 새로운 구분입니다. 이러한 차원에는 객관적인 것을 전제하지 않는 첫 번째 개념이 필요합니다. 따라서 문제는 "이 차원에서 첫 번째 개념은 무엇인가, 즉 절대적으로 순수한 주관적 확실성으로서의 진리를 어떤 개념에서 출발하여 결정할 수 있는가?"입니다. 이것이 바로 코기토입니다. 다른 개념들은 동일한 조건에 따라 문제에 대응하고 동일한 차원에 머물러야만, 그것들이 첫 번째 개념과 다리처럼 연결될 때에만 객관성을 획득할 수 있습니다. 여기서 객관성은 이미 존재하거나 이미 존재하는 것으로 인식되는 진리를 전제하기보다는 지식의 확실성을 전제로 합니다.

There is no point in wondering whether Descartes was right or wrong. Are implicit and subjective presuppositions more valid than explicit objective presuppositions? Is it necessary "to begin," and, if so, is it necessary to start from the point of view of a subjective certainty? Can thought as such be the verb of an I? There is no direct answer. Cartesian concepts can only be assessed as a function of their problems and their plane. In general, if earlier concepts were able to prepare a concept but not constitute it, it is because their problem was still trapped within other problems, and their plane did not yet possess its indispensable curvature or movements. And concepts can only be replaced by others if there are new problems and another plane relative to which (for example) "I" loses all meaning, the beginning loses all necessity, and the presuppositions lose all difference—or take on others. A concept always has the truth that falls to it as a function of the conditions of its creation. Is there one plane that is better than all the others, or problems that dominate all others? Nothing at all can be said on this point. Planes must be constructed and problems posed, just as concepts must be created. Philosophers do the best they can, but they have too much to do to know whether it is the best, or even to bother with this question. Of course, new concepts must relate to our problems, to our history, and, above all, to our becomings. But what does it mean for a concept to be of our time, or of any time? Concepts are not eternal, but does this mean they are temporal? What is the philosophical form of the problems of a particular time? If one concept is "better" than an earlier one, it is because it makes us aware of new variations and unknown resonances, it carries out unforeseen cuttings-out, it brings forth an Event that surveys [survole] us. But did the earlier concept not do this already? If one can still be a Platonist, Cartesian, or Kantian today, it is because one is justified in thinking that their concepts can be reactivated in our problems and inspire those concepts that need to be created. What is the best way to follow the great philosophers? Is it to repeat what they said or to do what they did, that is, create concepts for problems that necessarily change?

데카르트가 옳았는지 틀렸는지 궁금해할 필요는 없습니다. 암묵적이고 주체적인 전제가 명시적이고 객관적 전제보다 더 타당할까요? 과연 "시작"이 필요한가요? 그렇다면 주체적인 확실성의 관점에서 시작해야 하나요? 그런 식으로 생각한다는 것이 나(I)의 동사가 될 수 있을까요? 정답은 없습니다. 데카르트 개념들은 그들의 문제들과 그 차원의 함수로서만 측정될 수 있습니다. 일반적으로 이전의 개념들이 이 개념을 준비할 수는 있었지만 그것을 구성할 수 없었다면, 그것은 그들의 문제가 여전히 다른 문제들 안에 갇혀 있었고, 그들의 차원이 아직 필수적인 곡률이나 움직임을 가지고 있지 않았기 때문입니다. 그리고 개념들은 (예를 들어) '나'가 모든 의미를 잃고, 시작이 모든 필연성을 잃고, 전제가 모든 차이를 잃는 새로운 문제들과 상대적인 다른 차원이 있을 때만 다른 것으로 대체되거나 다른 것을 취할 수 있습니다. 개념은 항상 그 개념이 탄생한 조건의 함수로서 그 개념에 해당하는 진리를 가지고 있습니다. 다른 모든 것보다 더 나은 하나의 차원이 있을까요, 아니면 다른 모든 차원을 지배하는 문제가 있을까요? 이 점에 대해서는 아무것도 말할 수 없습니다. 개념이 창조되어야 하는 것처럼 차원도 구축되어야 하고 문제도 제기되어야 합니다. 철학자들은 최선을 다하지만, 그것이 최선인지 아닌지 알기에는 할 일이 너무 많아서 이 질문에 신경을 쓰기조차 힘듭니다. 물론 새로운 개념은 우리의 문제, 우리의 역사, 그리고 무엇보다도 우리의 되기와 관련이 있어야 합니다. 하지만 개념이 우리 시대, 혹은 어느 시대의 개념이라는 것은 무엇을 의미할까요? 개념은 영원하지 않지만, 이것이 일시적이라는 것을 의미할까요? 특정 시대의 문제들의 철학적 형태는 무엇일까요? 하나의 개념이 이전의 개념보다 "더 나은" 개념이라면, 그것은 새로운 변화와 미지의 공명들을 우리에게 인식시키고, 예기치 않은 단절을 수행하며, 우리를 비행[생존]하는 사건을 불러오기 때문입니다. 하지만 이전의 개념은 이미 이런 일을 하지 않았나요? 오늘날에도 플라톤주의자, 데카르트주의자, 칸트주의자가 될 수 있다면, 그것은 그들의 개념이 우리의 문제들 속에서 다시 활성화되어 새로운 개념들을 창조해낼 수 있는 영감을 정당화하여 생각하게 할 수 있기 때문입니다. 위대한 철학자들을 따르는 가장 좋은 방법은 무엇일까요? 그들이 말한 것을 반복하는 것일까요, 아니면 그들이 한 일을 하는 것, 즉 필연적으로 변화하는 문제들에 대한 개념을 창조하는 것일까요?

For this reason philosophers have very little time for discussion. Every philosopher runs away when he or she hears someone say, "Let's discuss this." Discussions are fine for roundtable talks, but philosophy throws its numbered dice on another table. The best one can say about discussions is that they take things no farther, since the participants never talk about the same thing. Of what concern is it to philosophy that someone has such a view, and thinks this or that, if the problems at stake are not stated? And when they are stated, it is no longer a matter of discussing but rather one of creating concepts for the undiscussible problem posed. Communication always comes too early or too late, and when it comes to creating, conversation is always superfluous. Sometimes philosophy is turned into the idea of a perpetual discussion, as "communicative rationality," or as "universal democratic conversation." Nothing is less exact, and when philosophers criticize each other it is on the basis of problems and on a plane that is different from theirs and that melt down the old concepts in the way a cannon can be melted down to make new weapons. It never takes place on the same plane. To criticize is only to establish that a concept vanishes when it is thrust into a new milieu, losing some of its components, or acquiring others that transform it. But those who criticize without creating, those who are content to defend the vanished concept without being able to give it the forces it needs to return to life, are the plague of philosophy. All these debaters and communicators are inspired by resentiment. They speak only of themselves when they set empty generalizations against one another. Philosophy has a horror of discussions. It always has something else to do. Debate is unbearable to it, but not because it is too sure of itself. On the contrary, it is its uncertainties that take it down other, more solitary paths. But in Socrates was philosophy not a free discussion among friends? Is it not, as the conversation of free men, the summit of Greek sociability? In fact, Socrates constantly made all discussion impossible, both in the short form of the contest of questions and answers and in the long form of a rivalry between discourses. He turned the friend into the friend of the single concept, and the concept into the pitiless monologue that eliminates the rivals one by one.

이런 이유로 철학자들은 토론할 시간이 별로 없습니다. 모든 철학자는 누군가 "토론하자"라는 말을 들으면 도망칩니다. 토론은 원탁 회의에서는 괜찮지만 철학은 다른 테이블에 주사위를 던집니다. 토론에 대해 말할 수 있는 가장 확실한 장점은 참가자들이 같은 주제에 대해 이야기하지 않기 때문에 더 이상 진전되지 않는다는 것입니다. 당면한 문제들이 언급되지 않았다면 누군가가 그러한 견해를 가지고 있고 이것 또는 저것을 생각하는 것이 철학에 무슨 관련이 있습니까? 그리고 그것들이 언급되면 그것은 더 이상 토론의 문제가 아니라 논의할 여지가 없는 문제들에 대한 개념을 만드는 문제입니다. 소통은 항상 너무 이르거나 늦게 이루어지며, 창조에 있어서 대화는 항상 불필요한 것입니다. 때때로 철학은 "소통하는 합리성" 또는 "보편적인 민주적 대화"와 같이 끊임없는 토론의 개념으로 바뀌기도 합니다. 덜 정확한 것은 없으며, 철학자들이 서로를 비판할 때 그것은 그들의 문제들과 다른 차원에서, 그리고 대포를 녹여 새로운 무기를 만들어내는 방식으로 낡은 개념을 녹여내는 차원에서 이루어집니다. 그것은 결코 같은 차원에서 일어나지 않습니다. 비판한다는 것은 하나의 개념이 새로운 환경으로 밀려나면서 그 구성 요소 중 일부를 잃거나 그것을 변화시키는 다른 요소를 획득할 때 사라진다는 것을 입증하는 것일 뿐입니다. 그러나 창조하지 않고 비판하는 사람들, 사라진 개념이 다시 삶을 되찾는 데 필요한 힘을 부여하지 않고 그것을 옹호하는 데 만족하는 사람들은 철학의 전염병입니다. 이 모든 토론자들과 소통자들은 분노에서 영감을 얻습니다. 그들은 서로에 맞서 공허한 일반화를 설정할 때만 자신에 대해 이야기합니다. 철학은 토론에 대한 공포를 가지고 있습니다. 철학에는 항상 다른 할 일이 있습니다. 철학이 토론을 견디지 못하는 이유는 철학이 스스로를 너무 확신하기 때문이 아닙니다. 오히려 그 불확실성 때문에 더 고독한 다른 길을 걷게 되는 것이죠. 하지만 소크라테스에게 철학은 친구들 간의 자유로운 토론이 아니었을까요? 자유로운 사람들의 대화로서 그리스 사교성의 정점이 아닐까요? 사실 소크라테스는 질문과 답변의 짧은 시합의 형식과 담론 간의 경쟁이라는 긴 형식 모두에서 모든 토론을 끊임없이 불가능하게 만들었습니다. 그는 친구를 하나의 개념의 친구로, 개념을 라이벌을 하나씩 제거하는 무자비한 독백으로 바꿨습니다.

Example 2

The Parmenides shows the extent to which Plato is master of the concept. The One has two components (being and nonbeing), phases of components (the One superior to being, equal to being, inferior to being; the One superior to nonbeing, equal to nonbeing), and zones of indiscernibility (in relation to itself, in relation to others). It is a model concept.

파르메니데스는 플라톤이 얼마나 개념의 대가인지를 보여줍니다. 일자는 두 가지 구성 요소들(존재와 비존재), 구성 요소들의 단계(존재보다 우월하고 존재와 같고 존재보다 열등한 일자; 비존재보다 우월하고 비존재와 같은 일자), 그리고 식별 불가능한 지대들(자신과 관련해서, 다른 것들과 관련해서)을 가지고 있습니다. 이것은 모델 개념입니다.

But is not the One prior to every concept? This is where Plato teaches the opposite of what he does: he creates concepts but needs to set them up as representing the uncreated that precedes them. He puts time into the concept, but it is a time that must be Anterior. He constructs the concept but as something that attests to the preexistence of an objectality [objectité], in the form of a difference of time capable of measuring the distance or closeness of the concept's possible constructor. Thus, on the Platonic plane, truth is posed as presupposition, as already there. This is the Idea. In the Platonic concept of the Idea, first takes on a precise sense, very different from the meaning it will have in Descartes: it is that which objectively possesses a pure quality, or which is not something other than what it is. Only Justice is just, only Courage courageous, such are Ideas, and there is an Idea of mother if there is a mother who is not something other than a mother (who would not have been a daughter), or of hair which is not something other than hair (not silicon as well). Things, on the contrary, are understood as always being something other than what they are. At best, therefore, they only possess quality in a secondary way, they can only lay claim to quality, and only to the degree that they participate in the Idea. Thus the concept of Idea has the following components: the quality possessed or to be possessed; the Idea that possesses it first, as unparticipable; that which lays claim to the quality and can only possess it second, third, fourth; and the Idea participated in, which judges the claims-the Father, a double of the father, the daughter and the suitors, we might say. These are the intensive ordinates of the Idea: a claim will be justified only through a neighborhood, a greater or lesser proximity it "has had" in relation to the Idea, in the survey of an always necessarily anterior time. Time in this form of anteriority belongs to the concept; it is like its zone. Certainly, the cogito cannot germinate on this Greek plane, this Platonic soil. So long as the preexistence of the Idea remains (even in the Christian form of archetypes in God's understanding), the cogito could be prepared but not fully accomplished. For Descartes to create this concept, the meaning of "first" must undergo a remarkable change, take on a subjective meaning; and all difference of time between the idea and the soul that forms it as subject must be annulled (hence the importance of Descartes's point against reminiscence, in which he says that innate ideas do not exist "before" but "at the same time" as the soul). It will be necessary to arrive at an instantaneity of the concept and for God to create even truths. The claim must change qualitatively: the suitor no longer receives the daughter from the father but owes her hand only to his own chivalric prowess -to his own method. Whether Malebranche can reactivate Platonic components on an authentically Cartesian plane, and at what cost, should be analyzed from this point of view. But we only wanted to show that a concept always has components that can prevent the appearance of another concept or, on the contrary, that can themselves appear only at the cost of the disappearance of other concepts. However, a concept is never valued by reference to what it prevents: it is valued for its incomparable position and its own creation.

하지만 일자는 모든 개념에 선행하지 않나요? 여기서 플라톤은 자신이 하는 일과 정반대로 가르칩니다: 그는 개념들을 창조하지만 개념들보다 선행하는 창조되지 않은 것을 표상하는 것으로 그것들을 설정해야 합니다. 그는 개념에 시간을 투입하지만 그 시간은 반드시 '이전'이어야 하는 시간입니다. 그는 개념을 구성하지만 객관성[객관성]의 선행실존을 증명하는 것으로서, 개념의 가능한 구축자와의 거리 또는 가까움을 측정할 수 있는 시간 차이의 형태로 개념을 구성합니다. 따라서 플라톤적 차원에서 진리는 이미 존재하는 것처럼 전제로서 제시됩니다. 이것이 바로 이데아입니다. 플라톤의 이데아 개념에서 이데아는 데카르트에서 갖는 의미와는 매우 다른 엄밀한 의미, 즉 객관적으로 순수한 질을 지니고 있는 것, 즉 다른 어떤 것이 아닌 것을 의미합니다. 정의만이 정의롭고 용기만이 용기 있는 것처럼, 만약 어머니 이외의 것이 아닌 어머니가 있다면 어머니에 대한 이데아가 있고(딸이었던 적이 없는), 머리카락 이외의 것이 아닌 머리카락에 대한 이데아가 있습니다( 역시 실리콘이 아닌). 반대로 사물들은 항상 자신이 아닌 다른 무엇으로 이해됩니다. 따라서 사물은 기껏해야 부차적인 방식으로만 질을 소유할 수 있으며, 이데아에 동참하는 한도 내에서만 질에 대한 소유권을 주장할 수 있습니다. 따라서 이데아의 개념은 다음과 같은 구성 요소들을 가지고 있습니다: 소유하고 있거나 소유해야 할 질; 참여 불가능한 것으로서 먼저 그것을 소유하는 이데아; 질에 대해 소유권을 주장하고 두 번째, 세 번째, 네 번째로만 소유할 수 있는 것; 그리고 그 주장을 판가름 하는 참여된 이데아 - 즉 우리는 아버지, 아버지의 이중인 딸과 구혼자들을 말할 수 있을 것입니다. 이것이 이데아의 강도적인 좌표입니다: 하나의 주장은 이웃을 통해서만, 이데아와의 관계에서 그것이 "가져왔던" 더 많거나 적은 근접성을 통해서만, 항상 필연적으로 앞선 시간의 조감 안에서 정당화될 것입니다. 이러한 선행성 형태의 시간은 개념에 속하며, 그것의 지대와 같습니다. 물론 코기토는 이 그리스적 차원, 이 플라톤적 토양에서 싹을 틔울 수 없습니다. 이데아의 선행실존이 남아 있는 한(심지어 신의 이해에서 원형이라는 기독교적 형태로도), 코기토는 준비될 수는 있지만 완전히 성취될 수는 없습니다. 데카르트가 이 개념을 창조하기 위해서는 '처음'의 의미가 현저한 변화를 거쳐 주체적 의미를 가져야 하며, 이데아와 그것을 주체로서 형성하는 영혼 사이의 모든 시간의 차이가 무효화되어야 합니다(따라서 선천적 이데아는 영혼보다 '전에' 존재하는 것이 아니라 '동시에' 존재한다고 말하는 데카르트의 회상에 반하는 지적의 중요성이 강조됩니다). 그것은 개념의 순간성에 도달하고 신이 진리들까지도 창조하기 위해 필요할 것입니다. 소유에 대한 권리는 질적으로 바뀌어야합니다 : 구혼자는 더 이상 아버지로부터 딸을 받지 않고 자신의 기사도 적 능력, 즉 자신의 방법에 의해서만 그녀를 맞이해야 합니다. 말브랑슈가 진정한 데카르트적 차원에서 플라톤적 구성 요소들을 재활성화할 수 있는지, 그리고 그 대가는 얼마인지는 이러한 관점에서 분석되어야 합니다. 그러나 우리는 개념이 항상 다른 개념의 출현을 막을 수 있는 구성 요소들을 가지고 있거나 반대로 다른 개념들의 소멸을 대가로 스스로 나타날 수 있다는 것을 보여주고 싶었을 뿐입니다. 그러나 개념은 결코 그것이 방지하는 것을 기준으로 가치화되지 않습니다: 그것은 그것의 비교할 수 없는 위치와 그 자체의 창조로 인해 가치화됩니다.

Suppose a component is added to a concept: the concept will probably break up or undergo a complete change involving, perhaps, another plane -at any rate, other problems. This is what happens with the Kantian cogito. No doubt Kant constructs a "transcendental" plane that renders doubt useless and changes the nature of the presuppositions once again. But it is by virtue of this very plane that he can declare that if the "I think" is a determination that, as such, implies an undetermined existence ("I am"), we still do not know how this undetermined comes to be determinable and hence in what form it appears as determined. Kant therefore "criticizes" Descartes for having said, "I am a thinking substance," because nothing warrants such a claim of the "I." Kant demands the introduction of a new component into the cogito, the one Descartes repressed -time. For it is only in time that my undetermined existence is determinable. But I am only determined in time as a passive and phenomenal self, an always affectable, modifiable, and variable self. The cogito now presents four components: I think, and as such I am active; I have an existence; this existence is only determinable in time as a passive self; I am therefore determined as a passive self that necessarily represents its own thinking activity to itself as an Other(Autre) that affects it. This is not another subject but rather the subject who becomes an other. Is this the path of a conversion of the self to the other person? A preparation for "I is an other"? A new syntax, with other ordinates, with other zones of indiscernibility, secured first by the schema and then by the affection of self by self [soi par soi], makes the "I" and the "Self" inseparable.

어떤 개념에 하나의 구성 요소가 추가된다고 가정해 보겠습니다: 그 개념은 아마도 해체되거나 다른 차원을 포함하는 완전한 변화를 겪게 될 것입니다 - 어쨌든 다른 문제가 발생할 수도 있습니다. 이것이 칸트의 코기토에서 일어나는 일입니다. 의심할 여지없이 칸트는 의심을 쓸모없게 만들고 전제들의 본질을 다시 한 번 바꾸는 "초월적" 차원을 구성합니다. 그러나 바로 이 차원 덕분에 그는 "나는 생각한다"가 확정되지 않은 존재("나는 있다")를 암시하는 확정이라면, 우리는 여전히 이 확정되지 않은 것이 어떻게 확정 가능하게 되는지, 따라서 어떤 형태로 확정된 것으로 나타나는지 알지 못한다고 선언할 수 있습니다. 따라서 칸트는 "나는 생각하는 실체"라고 말한 데카르트를 "비판"하는데, 그 이유는 "나"에 대한 그러한 주장을 보증하는 것은 아무것도 없기 때문입니다. 칸트는 코기토에 데카르트가 억압했던 새로운 요소, 즉 시간이라는 요소를 도입할 것을 요구합니다. 왜냐하면 확정되지 않은 나의 존재가 확정될 수 있는 것은 시간 속에서만 가능하기 때문입니다. 그러나 나는 수동적이고 현상에 불과한 자아, 항상 변화할 수 있고 수정 가능하며 가변적인 자아로서 시간 속에서만 확정됩니다. 코기토는 이제 네 가지 구성 요소를 제시합니다: 나는 생각한다, 따라서 나는 능동적이다; 나는 존재한다; 이 존재는 수동적 자아로서 시간 속에서만 확정 가능하다; 따라서 나는 자신에게 영향을 미치는 타자(Autre)로서 자신의 사고 활동을 반드시 자기 자신에게 표상시키는 수동적 자아로서 결정됩니다. 이것은 또 다른 주체가 아니라 오히려 타자가 되는 주체입니다. 이것이 자아가 타자로 전환되는 길일까요? "나는 타자다"를 위한 준비 과정일까요? 새로운 통사론, 다른 세로좌표들, 다른 불확정성의 지대들이 도식에 의해 먼저 확보된 다음, 자아에 의한 자아의 변용[soi par soi]에 의해 '나'와 '자아'를 분리할 수 없게 만든다.

The fact that Kant "criticizes" Descartes means only that he sets up a plane and constructs a problem that could not be occupied or completed by the Cartesian cogito. Descartes created the cogito as concept, but by expelling time as form of anteriority, so as to make it a simple mode of succession referring to continuous creation. Kant reintroduces time into the cogito, but it is a completely different time from that of Platonic anteriority. This is the creation of a concept. He makes time a component of a new cogito, but on condition of providing in turn a new concept of time: time becomes form of interiority with three components succession, but also simultaneity and permanence. This again implies a new concept of space that can no longer be defined by simple simultaneity and becomes form of exteriority. Space, time, and "I think" are three original concepts linked by bridges that are also junctions—a blast of original concepts. The history of philosophy means that we evaluate not only the historical novelty of the concepts created by a philosopher but also the power of their becoming when they pass into one another.

칸트가 데카르트를 "비판" 하는 것은 단지 그가 데카르트의 코기토가 점유하거나 완성할 수 없는 차원을 설정하고 문제를 구축한다는 것을 의미할 뿐입니다. 데카르트는 코기토를 개념으로 만들었지만, 시간을 선행성의 형태로 추방하여 계속되는 창조를 가리키는 단순한 연속의 방식으로 만들었습니다. 칸트는 코기토에 시간을 다시 도입했지만, 그것은 플라톤의 선험성과는 완전히 다른 시간입니다. 이것은 개념의 창조입니다. 그는 시간을 새로운 코기토의 구성 요소로 만들지만, 새로운 시간 개념을 제공한다는 전제하에 그렇습니다: 시간은 세 가지의 구성 요소, 즉 연속성, 동시성, 영속성을 가진 내면성의 형태가 됩니다. 이것은 다시 공간에 대한 새로운 개념을 암시하는데, 공간은 더 이상 단순한 동시성으로 정의할 수 없고 외재성의 형태가 됩니다. 공간, 시간, 그리고 '생각한다' 라는 세 가지 독창적인 개념은 교차점이기도 한 다리들로 연결된, 즉 독창적인 개념들의 폭발입니다. 철학의 역사는 한 철학자가 창조한 개념의 역사적 참신성뿐만 아니라 개념이 서로를 통과할 때 생기는 힘을 평가한다는 것을 의미합니다.

The same pedagogical status of the concept can be found everywhere: a multiplicity, an absolute surface or volume, self-referents, made up of a certain number of inseparable intensive variations according to an order of neighborhood, and traversed by a point in a state of survey. The concept is the contour, the configuration, the constellation of an event to come. Concepts in this sense belong to philosophy by right, because it is philosophy that creates them and never stops creating them. The concept is obviously knowledge -but knowledge of itself, and what it knows is the pure event, which must not be confused with the state of affairs in which it is embodied. The task of philosophy when it creates concepts, entities, is always to extract an event from things and beings, to set up the new event from things and beings, always to give them a new event: space, time, matter, thought, the possible as events.

개념의 동일한 교육적 지위는 모든 곳에서 찾을 수 있습니다 : 다양성, 절대 표면 또는 부피, 자기 참조, 이웃 순서에 따라 분리 할 수없는 특정 수의 강도적인 변이들로 구성되고 비행 상태의 한 지점에 의해 횡단되는 것입니다. 개념은 앞으로 일어날 사건의 윤곽, 구성, 별자리입니다. 이런 의미에서 개념들은 철학에 속하며, 철학은 개념들을 창조하고 그 창조를 멈추지 않기 때문입니다. 개념은 분명히 지식이지만 그 자체에 대한 지식이며, 그것이 아는 것은 순수한 사건이며, 그것이 체현된 상황과 혼동해서는 안됩니다. 개념들, 실체들을 창조할 때 철학의 임무는 항상 사물과 존재로부터 사건을 추출하고, 사물과 존재로부터 새로운 사건을 설정하고, 항상 공간, 시간, 물질, 사고, 가능한 것을 사건들로 새롭게 부여하는 것입니다.

It is pointless to say that there are concepts in science. Even when science is concerned with the same "objects" it is not from the viewpoint of the concept; it is not by creating concepts. It might be said that this is just a matter of words, but it is rare for words not to involve intentions and ruses. It would be a mere matter of words if it was decided to reserve the concept for science, even if this meant finding another word to designate the business of philosophy. But usually things are done differently. The power of the concept is attributed to science, the concept being defined by the creative methods of science and measured against science. The issue is then whether there remains a possibility of philosophy forming secondary concepts that make up for their own insufficiency by a vague appeal to the "lived." Thus Gilles-Gaston Granger begins by defining the concept as a scientific proposition or function and then concedes that there may, nonetheless, be philosophical concepts that replace reference to the object by correlation to a "totality of the lived" [totalité du vécu]. But actually, either philosophy completely ignores the concept, or else it enjoys it by right and at first hand, so that there is nothing of it left for science -which, moreover, has no need of the concept and concerns itself only with states of affairs and their conditions. Science needs only propositions or functions, whereas philosophy, for its part, does not need to invoke a lived that would give only a ghostly and extrinsic life to secondary, bloodless concepts. The philosophical concept does not refer to the lived, by way of compensation, but consists, through its own creation, in setting up an event that surveys the whole of the lived no less than every state of affairs. Every concept shapes and reshapes the event in its own way. The greatness of a philosophy is measured by the nature of the events to which its concepts summon us or that it enables us to release in concepts. So the unique, exclusive bond between concepts and philosophy as a creative discipline must be tested in its finest details. The concept belongs to philosophy and only to philosophy.

과학에 개념들이 있다고 말하는 것은 무의미합니다. 과학이 같은 '대상들'을 다룰 때에도 그것은 개념의 관점이 아니고 개념을 만들어내는 것도 아니기 때문입니다. 이것은 단지 말의 문제라고 말할 수도 있지만, 말에 의도들과 계략들이 포함되지 않는 경우는 드뭅니다. 만약 철학이라는 사업을 지칭할 다른 단어를 찾기 위해 과학에 개념을 맡기기로 결정했다면 그것은 단순한 말의 문제일 것입니다. 그러나 일반적으로 일은 다르게 이루어집니다. 개념의 힘은 과학으로 귀속되며, 개념은 과학의 창의적인 방법에 의해 정의되고 과학에 대항하여 측정됩니다. 그렇다면 문제는 철학이 "삶"에 대한 막연한 호소를 통해 자신의 부족함을 보완하는 이차적 개념을 형성할 가능성이 남아 있는지 여부입니다. 따라서 질-가스통 그랭거는 개념을 과학적 명제나 기능으로 정의하는 것으로 시작한 다음, 그럼에도 불구하고 "삶의 총체"[총체 뒤 베쿠]와의 상관관계로 대상에 대한 참조를 대체하는 철학적 개념이 있을 수 있다고 인정합니다. 그러나 실제로 철학은 이 개념을 완전히 무시하거나, 그렇지 않으면 그것은 처음부터 그것을 권리로 누리기 때문에 과학에 남겨주는 것은 아무것도 없으며, 더 나아가 과학은 개념이 필요없고 그들의 상황과 조건에만 신경을 씁니다. 과학은 명제나 기능만을 필요로 하는 반면, 철학은 그것의 부분으로서 오직 유령적이고 외재적인 생명을 이차적이고 피가 없는 개념으로 부여하기에 삶을 불러일으킬 필요가 없습니다. 철학적 개념은 보상의 방식으로 삶에 회부되는 것이 아니라 그 자체의 창조를 통해 모든 상황만큼이나 삶 전체를 비행하는 사건을 설정하는 것으로 구성됩니다. 모든 개념은 나름의 방식으로 사건을 형성하고 재구성합니다. 철학의 위대함은 그 개념이 우리를 소환하거나 개념들 속으로 풀어내게끔 하는 사건의 본성에 의해 측정됩니다. 따라서 창조적 학문으로서 개념들과 철학 사이의 독특하고 배타적인 유대는 가장 세밀한 부분에서 시험되어야 합니다. 개념은 철학에 속하며 철학에만 속합니다.

2. The plane of immanence

Philosophical concepts are fragmentary wholes that are not aligned with one another so that they fit together, because their edges do not match up. They are not pieces of a jigsaw puzzle but rather the outcome of throws of the dice. They resonate nonetheless, and the philosophy that creates them always introduces a powerful Whole that, while remaining open, is not fragmented: an unlimited One-All, an "Omnitudo" that includes all the concepts on one and the same plane. It is a table, a plateau, or a slice; it is a plane of consistency or, more accurately, the plane of immanence of concepts, the planomenon. Concepts and plane are strictly correlative, but nevertheless the two should not be confused. The plane of immanence is neither a concept nor the concept of all concepts. If one were to be confused with the other there would be nothing to stop concepts from forming a single one or becoming universals and losing their singularity, and the plane would also lose its openness. Philosophy is a constructivism, and constructivism has two qualitatively different complementary aspects: the creation of concepts and the laying out of a plane. Concepts are like multiple waves, rising and falling, but the plane of immanence is the single wave that rolls them up and unrolls them. The plane envelops infinite movements that pass back and forth through it, but concepts are the infinite speeds of finite movements that, in each case, pass only through their own components. From Epicurus to Spinoza (the incredible book) and from Spinoza to Michaux the problem of thought is infinite speed. But this speed requires a milieu that moves infinitely in itself -the plane, the void, the horizon. Both elasticity of the concept and fluidity of the milieu are needed.' Both are needed to make up "the slow beings" that we are.

철학적 개념은 서로의 가장자리가 일치하지 않기 때문에 서로 맞아떨어지지 않는 파편적인 전체입니다. 그것은 직소 퍼즐의 조각이 아니라 주사위를 던져 나온 결과에 불과합니다. 그럼에도 불구하고 그것들은 공명하며, 그것들을 창조하는 철학은 항상 열려 있으면서도 파편화되지 않은 강력한 전체, 즉 모든 개념을 하나의 동일한 차원에 포함하는 '전능자', 즉 무한한 하나-전체(One-All)를 소개합니다. 그것은 테이블, 고원 또는 조각이며, 일관성의 차원 또는 더 정확하게는 개념의 내재성의 차원, 즉 차원소입니다. 개념들과 차원은 엄밀한 상관관계가 있지만, 그럼에도 불구하고 이 둘을 혼동해서는 안 됩니다. 내재성의 차원은 개념도 아니고 모든 개념들의 개념도 아닙니다. 만약 둘 중 하나를 다른 것과 혼동한다면 개념들이 단일한 하나를 형성하거나 보편적인 것이 되는 것을 막을 수 없고, 그럼으로써 그들의 특이점을 잃게 될 것이며, 그 차원 또한 개방성을 잃게 될 것입니다. 철학은 구축주의이며, 구축주의는 두 가지 질적으로 다른 상호 보완적인 측면, 즉 개념들의 창조와 차원의 배치라는 두 가지 측면을 가지고 있습니다. 개념들은 다수의 파도와 같아서 상승과 하강을 반복하지만, 내재성의 차원은 개념들을 말아 올리고 펼치는 하나의 파도입니다. 차원은 무한한 움직임들을 감싸며 앞뒤로 통과하지만, 개념은 유한한 움직임의 무한한 속도이며 각각의 경우에 오직 자신의 구성 요소들만 통과합니다. 에피쿠로스에서 스피노자(놀라운 책-윤리학 5권)에 이르기까지, 그리고 스피노자에서 미쇼에 이르기까지 사유의 문제는 무한한 속도입니다. 그러나 이 속도를 위해서는 차원, 허공, 수평선 등 그 자체로 무한히 움직이는 환경이 필요합니다. 개념의 탄력성과 환경의 유동성이 모두 필요합니다. 이 두 가지가 모두 '느린 존재'인 우리를 구성하는 데 필요합니다.

Concepts are the archipelago or skeletal frame, a spinal column rather than a skull, whereas the plane is the breath that suffuses the separate parts. Concepts are absolute surfaces or volumes, formless and fragmentary, whereas the plane is the formless, unlimited absolute, neither surface nor volume but always fractal. Concepts are concrete assemblages, like the configurations of a machine, but the plane is the abstract machine of which these assemblages are the working parts. Concepts are events, but the plane is the horizon of events, the reservoir or reserve of purely conceptual events: not the relative horizon that functions as a limit, which changes with an observer and encloses observable states of affairs, but the absolute horizon, independent of any observer, which makes the event as concept independent of a visible state of affairs in which it is brought about. Concepts pave, occupy, or populate the plane bit by bit, whereas the plane itself is the indivisible milieu in which concepts are distributed without breaking up its continuity or integrity: they occupy it without measuring it out (the concept's combination is not a number) or are distributed without splitting it up. The plane is like a desert that concepts populate without dividing up. The only regions of the plane are concepts themselves, but the plane is all that holds them together. The plane has no other regions than the tribes populating and moving around on it. It is the plane that secures conceptual linkages with ever increasing connections, and it is concepts that secure the populating of the plane on an always renewed and variable curve.

개념들은 군도 또는 골격, 두개골이 아닌 척추인 반면 차원은 분리된 부분들에 숨을 불어넣는 숨결입니다. 개념들은 절대적인 표면들 또는 부피들이며 형태가 없고 파편적인 반면, 차원은 형태가 없고 무한한 절대이며 표면도 부피도 아니지만 항상 프랙탈입니다. 개념들은 기계의 구성과 같은 구체적인 배치물들이지만 차원은 이러한 배치물들이 부분으로서 작동하는 추상적인 기계입니다. 개념들은 사건이지만 차원은 사건들의 지평, 순수한 개념적 사건들의 저장소 또는 비축물입니다: 관찰자에 따라 변화하고 관찰 가능한 상황을 둘러싸는 한계로 기능하는 상대적 수평선이 아니라 관찰자와 무관한 절대적 수평선으로, 개념으로서의 사건이 유발되는 가시적 상황과 무관하게 만들어 줍니다. 개념들은 차원을 조금씩 포장하고, 점유하고, 채우는 반면, 차원 자체는 개념들이 그것의 연속성이나 온전성을 깨뜨리지 않고 분배되는 분할 불가능한 환경입니다: 개념들은 차원을 측정하지 않은 채로 점유하거나(개념의 조합은 숫자가 아닙니다) 그것을 쪼개지 않은 채로 분배됩니다. 차원은 개념들이 나누어지지 않고 채워지는 사막과 같습니다. 차원의 유일한 영역들은 개념 그 자체이지만, 차원은 개념들을 하나로 묶어주는 모든 것입니다. 차원에는 그 위에 거주하고 이동하는 부족들 외에는 다른 영역이 없습니다. 끊임없이 증가하는 연결들로 개념적 연결고리들을 확보하는 것은 차원이며, 항상 갱신되고 가변적인 곡선 위에서 차원을 채우는 것은 개념입니다.

The plane of immanence is not a concept that is or can be thought but rather the image of thought, the image thought gives itself of what it means to think, to make use of thought, to find one's bearings in thought. It is not a method, since every method is concerned with concepts and presupposes such an image. Neither is it a state of knowledge on the brain and its functioning, since thought here is not related to the slow brain as to the scientifically determinable state of affairs in which, whatever its use and orientation, thought is only brought about. Nor is it opinions held about thought, about its forms, ends, and means, at a particular moment. The image of thought implies a strict division between fact and right: what pertains to thought as such must be distinguished from contingent features of the brain or historical opinions. Quid juris? -can, for example, losing one's memory or being mad belong to thought as such, or are they only contingent features of the brain that should be considered as simple facts? Are contemplating, reflecting, or communicating anything more than opinions held about thought at a particular time and in a particular civilization? The image of thought retains only what thought can claim by right. Thought demands "only" movement that can be carried to infinity. What thought claims by right, what it selects, is infinite movement or the movement of the infinite. It is this that constitutes the image of thought.

내재성의 차원은 생각하거나 생각될 수 있는 개념이 아니라 사유의 이미지, 즉 사유한다는 것, 사유를 활용한다는 것, 사유에서 자신의 방향을 찾는다는 것이 무엇을 의미하는지에 대해 사유가 스스로 부여하는 이미지입니다. 모든 방법은 개념과 관련이 있고 그러한 이미지를 전제로 하기 때문에 그것은 방법이 아닙니다. 여기서의 사유는 그 사용과 방향이 무엇이든, 오직 사유를 불러일으키는 과학적으로 결정 가능한 상태의 느린 뇌와 관련이 없기 때문에 뇌와 그 기능에 대한 지식의 상태도 아닙니다. 또한 그것은 특정 순간에 사유의 형태, 목적, 수단을 결정하는 의견들도 아닙니다. 사유의 이미지는 사실과 옳음 사이의 엄격한 구분을 의미합니다. 즉, 사유와 관련된 것은 뇌의 우연한 특징이나 역사적 의견들과 구별되어야 합니다. 권리의 문제? -예를 들어, 기억을 잃거나 화를 내는 것도 사유에 속할 수 있을까요, 아니면 단순한 사실로 간주해야 하는 뇌의 우연적 특징일 뿐일까요? 관조, 반성, 혹은 의사소통은 특정 시대, 특정 문명에서 사유에 대해 가졌던 의견 이상의 무엇일까요? 사유의 이미지는 사유가 권리로 주장할 수 있는 것만을 유지합니다. 사유는 무한대로 나아갈 수 있는 '유일한' 움직임을 요구합니다. 사유가 권리로서 주장하는 것, 그것이 선택하는 것은 무한한 운동 또는 무한의 운동입니다. 이것이 바로 사유의 이미지를 구성하는 것입니다.

Movement of the infinite does not refer to spatiotemporal coordinates that define the successive positions of a moving object and the fixed reference points in relation to which these positions vary. "To orientate oneself in thought" implies neither objective reference point nor moving object that experiences itself as a subject and that, as such, strives for or needs the infinite. Movement takes in everything, and there is no place for a subject and an object that can only be concepts. It is the horizon itself that is in movement: the relative horizon recedes when the subject advances, but on the plane of immanence we are always and already on the absolute horizon. Infinite movement is defined by a coming and going, because it does not advance toward a destination without already turning back on itself, the needle also being the pole. If "turning toward" is the movement of thought toward truth, how could truth not also turn toward thought? And how could truth itself not turn away from thought when thought turns away from it? However, this is not a fusion but a reversibility, an immediate, perpetual, instantaneous exchange-a lightning flash. Infinite movement is double, and there is only a fold from one to the other. It is in this sense that thinking and being are said to be one and the same. Or rather, movement is not the image of thought without being also the substance of being. When Thales's thought leaps out, it comes back as water. When Heraclitus's thought becomes polemos, it is fire that retorts. It is a single speed on both sides: "The atom will traverse space with the speed of thought." The plane of immanence has two facets as Thought and as Nature, as Nous and as Physis. That is why there are always many infinite movements caught within each other, each folded in the others, so that the return of one instantaneously relaunches another in such a way that the plane of immanence is ceaselessly being woven, like a gigantic shuttle. To turn toward does not imply merely to turn away but to confront, to lose one's way, to move aside. Even the negative produces infinite movements: falling into error as much as avoiding the false, allowing oneself to be dominated by passions as much as overcoming them. Diverse movements of the infinite are so mixed in with each other that, far from breaking up the One-All of the plane of immanence, they constitute its variable curvature, its concavities and convexities, its fractal nature as it were. It is this fractal nature that makes the planomenon an infinite that is always different from any surface or volume determinable as a concept. Every movement passes through the whole of the plane by immediately turning back on and folding itself and also by folding other movements or allowing itself to be folded by them, giving rise to retroactions, connections, and proliferations in the fractalization of this infinitely folded up infinity (variable curvature of the plane). But if it is true that the plane of immanence is always single, being itself pure variation, then it is all the more necessary to explain why there are varied and distinct planes of immanence that, depending upon which infinite movements are retained and selected, succeed and contest each other in history. The plane is certainly not the same in the time of the Greeks, in the seventeenth century, and today (and these are still vague and general terms): there is neither the same image of thought nor the same substance of being. The plane is, therefore, the object of an infinite specification so that it seems to be a One-All only in cases specified by the selection of movement. This difficulty concerning the ultimate nature of the plane of immanence can only be resolved step by step.

무한의 움직임은 움직이는 대상의 연속적인 위치들을 규정하는 시공간적 좌표들과 그 위치들이 변화하는 고정된 기준점들을 의미하지 않습니다. '사유의 방향을 잡는다'는 것은 객관적인 기준점도 아니고, 스스로를 주체로서 경험하며 무한을 추구하거나 필요로 하는 움직이는 대상을 의미하지도 않습니다. 움직임은 모든 것을 받아들이며, 단지 개념들일 수 밖에 없는 주체와 객체의 자리는 존재하지 않습니다. 운동하는 것은 지평 그 자체입니다: 주체가 전진하면 상대적 지평은 후퇴하지만, 내재성의 차원에서 우리는 항상 그리고 이미 절대적 지평에 있습니다. 무한한 움직임은 이미 자신을 향해 돌아서지 않고는 목적지를 향해 전진하지 않기 때문에 오고 가는 것에 의해 정의되며, 따라서 바늘은 극이기도 합니다. '향함'이 진리를 향한 사유의 움직임이라면, 어떻게 진리도 사유를 향하지 않을 수 있겠습니까? 그리고 사유가 진리로부터 돌아설 때 진리 자체가 어떻게 사유로부터 돌아서지 않을 수 있겠습니까? 그러나 이것은 융합이 아니라 가역성, 즉 즉각적이고 영속적이며 순간적인 교환, 즉 번개처럼 번쩍이는 것입니다. 무한한 움직임은 이중이며, 한 쪽에서 다른 쪽으로의 접힘만 있을 뿐입니다. 이런 의미에서 사유와 존재는 하나라고 할 수 있습니다. 아니, 오히려 움직임은 존재의 실체 없이는 사유의 이미지가 아닙니다. 탈레스의 생각이 밖으로 튀어나가면 그것은 물처럼 되돌아옵니다. 헤라클레이토스의 사유가 논쟁이 될 때 이에 맞서는 것은 불입니다. 양쪽 모두 하나의 속도입니다: "원자는 사유의 속도로 공간을 횡단한다." 내재성의 차원은 생각과 자연, 이성과 자연이라는 두 가지 측면을 가지고 있습니다. 그렇기 때문에 항상 수많은 무한한 움직임이 서로 안에서 포착되고, 서로가 서로에게 접혀서 하나의 회귀가 다른 하나를 순간적으로 다시 발사하는 방식으로 내재성의 차원은 거대한 셔틀처럼 끊임없이 직조되고 있습니다. 방향을 전환한다는 것은 단순히 외면하는 것이 아니라 직면하고, 길을 잃고, 옆으로 비켜가는 것을 의미합니다. 부정적인 것조차도 무한한 움직임을 만들어냅니다: 거짓을 피하는 것만큼이나 오류에 빠지고, 정념을 극복하는 것만큼이나 정념에 지배당하는 자신을 허용합니다. 무한의 다양한 움직임은 서로 뒤섞여서 내재성의 차원의 하나-모두를 해체하는 것이 아니라, 그 가변적 곡률, 오목함과 볼록함, 프랙탈적 본성을 그대로 구성합니다. 이 프랙탈적 본성이 차원소를 개념으로 규정할 수 있는 어떤 표면이나 부피와는 항상 다른 무한한 것으로 만듭니다. 모든 움직임은 즉시 다시 회전하여 자신을 접고 다른 움직임들을 접거나 그들에 의해 접히게 함으로써 차원 전체를 통과하며, 무한히 접혀진 무한(차원의 가변 곡률)의 프랙탈화 속에서 반작용, 연결, 증식을 일으킵니다. 그러나 내재성의 차원이 항상 단일하고 그 자체가 순수한 변화라는 것이 사실이라면, 어떤 무한한 움직임이 유지되고 선택되는지에 따라 역사에서 서로 성공하고 경쟁하는 다양하고 구별되는 내재성의 차원이 존재하는 이유를 설명하는 것이 더욱 필요합니다. 차원은 그리스인 시대와 17세기, 그리고 오늘날(여전히 모호하고 일반적인 용어이지만) 동일하지 않습니다: 동일한 사유의 이미지도 동일한 존재의 실체도 존재하지 않습니다. 따라서 차원은 무한한 구체화의 대상이기 때문에 운동의 선별에 의해 구체화된 경우에만 하나-전부인 것처럼 보입니다. 내재성의 차원의 궁극적 본성에 관한 이 난제는 단계적으로 해결될 수 있을 뿐입니다.

It is essential not to confuse the plane of immanence and the concepts that occupy it. Although the same elements may appear twice over, on the plane and in the concept, it will not be in the same guise, even when they are expressed in the same verbs and words. We have seen this for being, thought, and one: they enter into the concept's components and are themselves concepts, but they belong to the plane quite differently as image or substance. Conversely, truth can only be defined on the plane by a "turning toward" or by "that toward which thought turns"; but this does not provide us with a concept of truth. If error itself is an element that by right forms part of the plane, then it consists simply in taking the false for the true (falling); but it only receives a concept if we determine its components (according to Descartes, for example, the two components of a finite understanding and an infinite will). Movements or elements of the plane, therefore, will seem to be only nominal definitions in relation to concepts so long as we disregard the difference in nature between plane and concepts. But in reality, elements of the plane are diagrammatic features, whereas concepts are intensive features. The former are movements of the infinite, whereas the latter are intensive ordinates of these movements, like original sections or differential positions: finite movements in which the infinite is now only speed and each of which constitutes a surface or a volume, an irregular contour marking a halt in the degree of proliferation. The former are directions that are fractal in nature, whereas the latter are absolute dimensions, intensively defined, always fragmentary surfaces or volumes. The former are intuitions, and the latter intensions. The grandiose Leibnizian or Bergsonian perspective that every philosophy depends upon an intuition that its concepts constantly develop through slight differences of intensity is justified if intuition is thought of as the envelopment of infinite movements of thought that constantly pass through a plane of immanence. Of course, we should not conclude from this that concepts are deduced from the plane: concepts require a special construction distinct from that of the plane, which is why concepts must be created just as the plane must be set up. Intensive features are never the consequence of diagrammatic features, and intensive ordinates are not deduced from movements or directions. Their correspondence goes beyond even simple resonances and introduces instances adjunct to the creation of concepts, namely, conceptual personae.

내재성의 차원과 그것을 점유하는 개념을 혼동하지 않는 것이 필수적입니다. 동일한 요소들이 차원과 개념에서 두 번 나타날 수 있지만, 동일한 동사와 단어로 표현되더라도 동일한 모습이 아닐 것입니다. 우리는 존재, 사유, 하나에 대해 이를 확인했습니다: 이들은 개념의 구성 요소들로 들어가며 그들 자체가 개념들이지만, 그들이 이미지나 실체로서 차원에 속하는 것은 상당히 다릅니다. 반대로 진리는 차원 위에서 오직 "향하는 것" 또는 "생각이 향하는 것"에 의해서만 정의될 수 있지만, 이것은 우리에게 진리라는 개념을 제공하지 않습니다. 만약 오류 자체가 차원의 일부를 형성하는 요소라면, 그것은 단순히 참을 위해 거짓을 취하는(떨어지는) 것으로 구성되지만, 우리가 그 구성 요소(예를 들어 데카르트에 따르면 오류는 유한한 이해와 무한한 의지의 두 가지 구성 요소를 가진다)를 결정할 때만 개념을 얻게 됩니다. 따라서 차원과 개념의 본성상의 차이를 무시하는 한, 차원의 움직임이나 요소는 개념과 관련하여 명목상의 정의에 불과한 것처럼 보일 것입니다. 그러나 현실에서 차원의 요소는 다이어그램적 특질들인 반면 개념은 강도적 특질들입니다. 전자는 무한의 움직임인 반면, 후자는 원근법이나 미분 위치들처럼 이러한 움직임들의 강도적인 좌표입니다: 무한은 이제 속도일 뿐이고 각각은 표면이나 부피를 구성하는 유한한 움직임, 확산의 정도가 멈추는 것을 나타내는 불규칙한 윤곽선입니다. 전자는 본성상 프랙탈적인 방향인 반면, 후자는 절대적인 차원(dimension)들이고, 강도적으로 정의되며 항상 파편적인 표면 또는 부피입니다. 전자는 직관들이고 후자는 강도/의도들입니다. 모든 철학은 직관에 의존하며 그것의 개념들은 약간의 강도의 차이를 통해 끊임없이 발전한다는 라이프니츠나 베르그송의 원대한 관점은 직관이 내재성의 평면을 끊임없이 통과하는 무한한 사유의 움직임의 포괄이라고 생각한다면 정당화될 수 있습니다. 물론 이것으로부터 개념들이 평면으로부터 연역된다는 결론을 내려서는 안 됩니다: 개념들은 평면과 구별되는 특별한 구축을 필요로 하기 때문에 평면이 설정되어야 하듯이 개념들도 만들어져야 합니다. 강도적 특질들은 다이어그램적 특질들의 결과물이 아니며 강도적 좌표들은 움직임이나 방향에서 연역되지 않습니다. 이들의 대응은 단순한 공명을 넘어 개념 생성에 부가적인 사례들, 즉 개념적 페르소나를 도입합니다.

If philosophy begins with the creation of concepts, then the plane of immanence must be regarded as prephilosophical. It is presupposed not in the way that one concept may refer to others but in the way that concepts themselves refer to a nonconceptual understanding. Once again, this intuitive understanding varies according to the way in which the plane is laid out. In Descartes it is a matter of a subjective understanding implicitly presupposed by the "I think" as first concept; in Plato it is the virtual image of an already-thought that doubles every actual concept. Heidegger invokes a "preontological understanding of Being," a "preconceptual" understanding that seems to imply the grasp of a substance of being in relationship with a predisposition of thought. In any event, philosophy posits as prephilosophical, or even as nonphilosophical, the power of a One-All like a moving desert that concepts come to populate. Prephilosophical does not mean something preexistent but rather something that does not exist outside philosophy, although philosophy presupposes it. These are its internal conditions. The nophilosophical is perhaps closer to the heart of philosophy than philosophy itself, and this means that philosophy cannot be content to be understood only philosophically or conceptually, but is addressed essentially to non-philosophers as well. We will see that this constant relationship with nonphilosophy has various features. According to this first feature, philosophy defined as the creation of concepts implies a distinct but inseparable presupposition. Philosophy is at once concept creation and instituting of the plane. The concept is the beginning of philosophy, but the plane is its instituting. The plane is clearly not a program, design, end, or means: it is a plane of immanence that constitutes the absolute ground of philosophy, its earth or deterritorialization, the foundation on which it creates its concepts. Both the creation of concepts and the instituting of the plane are required, like two wings or fins.

철학이 개념의 생성에서 시작한다면, 내재성의 평면은 선철학적인 것으로 간주되어야 합니다. 그것은 하나의 개념이 다른 것들을 지칭하는 방식이 아니라 개념들 스스로가 비개념적 이해로 회부되는 방식을 전제로 합니다. 다시 한 번 말하지만, 이러한 직관적 이해는 평면이 배치되는 방식에 따라 달라집니다. 데카르트에서는 첫 번째 개념으로서 "나는 생각한다"가 암묵적으로 전제하는 주체적 이해의 문제이고, 플라톤에서는 모든 현실화된 개념을 이중화하는 것은 이미 사유된 것의 가상 이미지입니다. 하이데거는 "존재에 대한 선존재론적 이해", 즉 사유의 성향과 관계에 있는 존재의 실체를 파악하는 것을 암시하는 것처럼 보이는 "전개념적" 이해를 불러일으킵니다. 어쨌든 철학은 개념들이 채워지는 움직이는 사막과 같은 하나-전체의 힘을 선철학적인 것으로, 또는 심지어 비철학적인 것으로 가정합니다. 선철학적인 것은 선재하는 무언가를 의미하는 것이 아니라 철학이 전제하지만 철학 외부에 존재하지 않는 무언가를 의미합니다. 이것이 철학의 내적 조건입니다. 비철학적인 것은 어쩌면 철학 자체보다 철학의 핵심에 더 가깝고, 이는 철학이 철학적 또는 개념적으로만 이해되는 것으로 만족할 수 없으며 철학자가 아닌 사람들에게도 본질적으로 다뤄진다는 것을 의미합니다. 이러한 비철학과의 끊임없는 관계에는 여러 가지 특질이 있음을 알 수 있습니다. 첫 번째 특질에 따르면, 개념의 창조로 정의되는 철학은 구별되지만 분리할 수 없는 전제를 내포하고 있습니다. 철학은 개념의 창조이자 동시에 평면의 성립입니다. 개념은 철학의 시작이지만 평면은 그것의 설립입니다. 평면은 분명히 프로그램, 설계, 목적, 수단이 아닙니다: 그것은 철학의 절대적 토대, 즉 개념을 창조하는 토대인 내재성의 평면, 즉 대지 또는 탈영토화를 구성하는 평면입니다. 개념의 창조와 평면의 확립은 두 개의 날개나 지느러미처럼 모두 필요합니다.

Thinking provokes general indifference. It is a dangerous exercise nevertheless. Indeed, it is only when the dangers become obvious that indifference ceases, but they often remain hidden and barely perceptible, inherent in the enterprise. Precisely because the plane of immanence is prephilosophical and does not immediately take effect with concepts, it implies a sort of groping experimentation and its layout resorts to measures that are not very respectable, rational, or reasonable. These measures belong to the order of dreams, of pathological processes, esoteric experiences, drunkenness, and excess. We head for the horizon, on the plane of immanence, and we return with bloodshot eyes, yet they are the eyes of the mind. Even Descartes had his dream. To think is always to follow the witch's flight. Take Michaux's plane of immanence, for example, with its infinite, wild movements and speeds. Usually these measures do not appear in the result, which must be grasped solely in itself and calmly. But then "danger" takes on another meaning: it becomes a case of obvious consequences when pure immanence provokes a strong, instinctive disapproval in public opinion, and the nature of the created concepts strengthens this disapproval. This is because one does not think without becoming something else, something that does not think -an animal, a molecule, a particle-and that comes back to thought and revives it.

생각하는 것은 전반적인 무관심을 유발합니다. 그럼에도 불구하고 이는 위험한 일입니다. 실제로 무관심이 멈추는 것은 위험이 명백해졌을 때이지만, 위험은 대개 숨겨져 있고 거의 인식할 수 없는 상태로 조직에 내재되어 있습니다. 내재성의 평면은 선철학적이고 개념들에 즉시 적용되지 않기 때문에 일종의 더듬어 보는 실험을 의미하며, 그것의 배치는 그다지 존경할 만하거나 이성적이거나 합리적이지 않은 측정들에 의존합니다. 이러한 측정들은 꿈의 질서, 병리학적인 과정들, 밀교적인 경험들, 술 취함과 과잉의 질서에 속합니다. 우리는 지평선, 내재성의 평면으로 향하고 충혈된 눈으로 돌아오지만, 그 눈은 마음의 눈입니다. 데카르트에게도 꿈이 있었습니다. 생각한다는 것은 언제나 마녀의 비행을 따라가는 것입니다. 예를 들어, 무한하고 거친 움직임과 속도를 가진 미쇼의 내재성의 평면을 생각해 보세요. 일반적으로 이러한 측정들은 결과에 나타나지 않으므로 오로지 그 자체로 침착하게 파악되어야 합니다. 그러나 "위험"은 또 다른 의미를 갖습니다 : 순수한 내재성이 여론에서 강력하고 본능적인 반감을 불러 일으키고 창조된 개념의 본성이 이러한 반감을 강화할 때 명백한 결과들의 경우가 됩니다. 왜냐하면 사람은 동물, 분자, 입자 등 사유하지 않는 다른 무언가가 되지 않고는 사유하지 않으며, 사유로 돌아와서 그것을 되살리기 때문입니다.